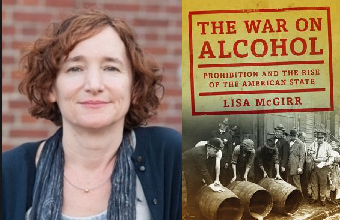

Editor’s Note: Today’s post comes from contributing editor Dr. Miriam Kingsberg Kadia , professor of history at the University of Colorado, Boulder. In it, she brings a global focus to drug and alcohol history and reviews Lisa McGirr’s book on federal Prohibition. Enjoy!

In addition to making this significant contribution to U.S. historiography, The War on Alcohol also opens the door to a more global treatment of the anti-intoxicants movement. The book breaks with the scholarly convention of understanding Prohibition as a peculiarly American phenomenon, born of the distinctive demographic clash between predominantly urban-based immigrant and minority cultures, and mainly rural, Protestant moral righteousness and nativism. Instead, it suggests important comparisons and linkages between anti-alcohol and anti-narcotics movements worldwide.

Paralleling the expansion of American federal power in the 1920s was the tightening of imperial control over much of the world. For most empires of the time (including the United States), the regulation of intoxicants served as a key plank within the mission civilisatrice, or the ideology that located imperial legitimacy in the “uplift” of the subject population towards “modern” Western norms. Yet even as colonial authorities waged a rhetorical war against the “backwards” phenomenon of addiction, they also profited from taxes levied on the sale of alcohol and drugs. In many colonies in Asia, public sales of opium furnished a third or more of the annual budget of the state. Imperialism was riven by an unyielding contradiction between the need for revenue from intoxicants on the one hand, and dependence on the ideological justification of control on the other.

Much like the war on alcohol birthed the American carceral state, proscription of intoxicants similarly served as a pretext to increase police and military capacity in imperial territories. For example, the self-appointed mission to suppress the allegedly “Chinese” problem of opium consumption allowed Japan to grow its consular and state forces in leaseholds on mainland China. These units ultimately fought side by side with Japanese army troops in the 1931 invasion of Manchuria. The result of this undeclared war was the establishment of the so-called puppet state of Manchukuo—like Prohibition, a “great experiment” of thirteen years’ duration (1932-1945).

To support her argument about the augmentation of state power in the 1920s, McGirr explores the relatively neglected aspect of enforcing Prohibition through case studies of two very different settings: the immigrant-heavy city of Chicago, and rural Virginia, dominated by African-American descendants of slaves and “poor whites.” Deconstructing cherished popular myths of almost comically bumbling police agents that were no match for swashbuckling and charismatic bootleggers, she shows that enforcement was anything but a joke for the disenfranchised. Alcohol consumption, or the stereotype thereof, formed a way to attack social Others—immigrants, Catholics and Jews, city-dwellers, the poor, etc. Prohibition was a race war, a class war, and a geography war, largely tolerating alcohol use among upper-class, native-born white Protestants (including some members of the Ku Klux Klan) while offering a pretext to penalize and marginalize stigmatized groups. In the empires that flourished across the same decades, (ascribed) addiction to narcotics similarly functioned as a means of criminalizing and controlling colonial Others. Members of the ruling group caught using narcotics were generally regarded as piteous racial failures and provided with medical treatment. Subject offenders, viewed as incorrigible, faced imprisonment or flogging, sometimes to the point of death. From its origins in the Prohibition era, the war on intoxicants has long offered a particularly sharp lens through which to glimpse the power dynamics among different (constructed) social groups.

Though the list of similarities between Prohibition in the U.S. and the anti-narcotics crusade beyond it might go on, McGirr gestures not only to comparison but also to connection. In her argument, a domestic and international prohibition regime emerged simultaneously and symbiotically with the American ban on alcohol. The crusades against liquor and drugs were rhetorically linked through the metaphor of addiction as slavery—a transformative experience and potent memory in many parts of the early twentieth-century world. Anti-narcotics crusaders often cited the successful enactment of Prohibition as an inspiration to their work. Yet although temperance movements generally reinforced each other, early twentieth-century perspectives on intoxicants sometimes placed anti-narcotics and anti-alcohol activists at cross purposes. While generally deploring the use of intoxicants, many believed that their use was “natural” or inevitable and that each people gravitated to a characteristic substance. These intoxicants could be arranged in a hierarchy reflecting the racial status of its purported consumers. For example, the “inferior” Chinese were associated with opium smoking; “superior” whites with alcohol. Accordingly, some anti-narcotics crusaders called for the replacement of opium with alcohol consumption in East and Southeast Asia as a step towards “civilizing” colonized populations.

The historiography of intoxicants has developed considerably in recent decades. Works by McAllister (2000), Davenport-Hines (2003), Gootenberg (2008), Courtwright (2009), and others have led the way towards a global history of narcotics and the fight to suppress them. Meanwhile, a comprehensive picture of alcohol and the temperance movement has emerged in the scholarship of authors including McGovern (2009), Tyrell (2010), and Harms (2014). An ambitious and important contribution to the literature, The War on Alcohol suggests the exciting future possibility of an embracing joint history of alcohol and drugs.