The State of the Art: The Malcolms’ Examination of Straight, Incorporated, Part 3

- Marcus Chatfield

- Jul 14, 2016

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a five-part series from Marcus Chatfield, a regular contributor to Points. Here he continues his examination of Straight, Inc., the controversial adolescent drug treatment program that existed from 1976 to 1993.

Beginning in 1976, the original design of Straight’s milieu was a slightly modified version of The Seed Inc., a program whose methods were also compared to “brainwashing” in the Congressional report, Individual Rights and the Federal Role in Behavior Modification (1974). Specific details about the origins of the actual design of The Seed program are elusive; it was one of many programs initiated in the late 1960s that implemented an array of group methods attributed to those developed by adult members of the therapeutic community, Synanon, founded in 1957 for the treatment of heroin addiction.

But the controversy over “brainwashing” in adolescent reform programs is older than any of the programs that grew out of Synanon; it seems to have started in 1962, over concerns about the Provo Experiment in Delinquency Rehabilitation at the Pinehills Center in Utah County, Utah. According to authors LaMar Empey and Maynard Erickson in their book, The Provo Experiment (1972), in November, 1962, at least one county commissioner had voiced concerns about public funding for the program because it seemed similar to “communist brainwashing.”

Earlier than these concerns about funding decisions are perhaps the first published concerns about the safety and ethics of “brainwashing” methods applied to American youths in a treatment setting. They came from Professor Whitney H. Gordon of Ball State Teachers College, in a letter to the editor of The American Sociological Review. His letter and a response by the directors of the Provo Experiment, LaMar Empey and Jerome Rabow, of Brigham Young University, were published in April, 1962, with the title: “Communist Rectification Programs and Delinquency Rehabilitation Programs: A Parallel?”

Professor Gordon was concerned about values, ethics and the precedent set by the use of methods which, he said, seemed “Orwellian” and “ghoulish” when used by communists:

One sees the leverage of the group being applied to the individual by way of public confessions, the demand for candor, the infinite patience and inscrutability of authority. There appears the “carrot and stick” technique along with the utilization of role disruption and social anxiety as motivating forces. Beyond that, one is reminded how systematically and thoroughly the integrity of psychological privacy is undermined.

Empey and Rabow responded quite frankly:

Professor Gordon is correct regarding the Provo Experiment and the Communists: there are parallels between the two programs. However, a recognition of this fact does not permit any simple conclusion as to what should be done.

First, they point out that there are also parallels between these techniques and accepted practices in religion, politics, medicine and psychology. They claim that there are forms of “brainwashing” in all of the above – in any the attempt “to change perceptions, attitudes and behavior through emotional stress, confessions, the presentation of new alternatives, followed sometimes by analyses.” They point out that other methods of juvenile reform are largely ineffective and they claim that the problem with the Communists’ use of these methods is that the victims did not understand the objectives of their captors and didn’t understand the means by which the objectives would be realized.

Thus, it is one thing to break a person down under intolerable stress and quite another to use this stress positively, not only to modify perceptions, but to permit a greater susceptibility for the examination of new alternatives, skills, and opportunities.

They conclude with, “There is no reason why stress cannot be used constructively,” and, “It is a matter of opinion whether individuality is really lost in the process, or whether the means used are unethical.”

The Provo Experiment was based on an earlier study that used similar small-group methods which probably predate the term,“brainwashing.” The New Jersey Experimental Project for the Treatment of Youthful Offenders at Highfields formally launched in 1950 and utilized small-group methods developed by Dr. F. Lovell Bixby and Lloyd W. McCorkle that would become controversial when used at Provo.

The “Highfields Experiment” in New Jersey was based on an even earlier study in “Guided Group Interaction” methods that were initiated and developed in the 1940s at the Fort Knox Rehabilitation Center by Dr. Alexander Wolf. During World War II, a “comprehensive group therapy program that embraced all aspects of living” was developed there for the reform of recalcitrant American soldiers (McKorkle, Elias, Bixby, 1958, p 73).

The ethical questions about “brainwashing” in treatment settings, first posed more than fifty years ago, are still relevant and still controversial today. But the discussion has changed as cultural values have shifted. Trauma-informed critics today tend to focus on iatrogenic effects rather than the violation of “American” values, and proponents spoke more candidly (and eloquently) about the therapeutic use of “brainwashing” methods during early 1960s than they have since the late 1960s, when programs using these methods started to appear all over the United States.

Straight’s executives were not so fearless and forthright as Empey, Rabow, Schein or Dederich; by the early 1980s, the American public associated “brainwashing” with cults and violence. The “B” word was a scary reminder of Charles Manson, Patty Hearst, Jim Jones and the People’s Temple massacre in Guyana. In late 1978, Charles Dederich ordered the murder of one of Synanon’s adversaries, Paul Morantz, leading to the famous picture of the giant rattlesnake his members had placed in Morantz’s mailbox, rattle removed. Morantz was bitten by the snake and hospitalized, but fortunately survived the attack. This sensational story was the focus of a media frenzy until 1980, when Dederich plead “no contest” to the charge of conspiracy to commit murder. In the early 1960s, experts argued that “brainwashing” could be used for good or “evil” purposes, but by the time Straight was poised to become a national franchise, these associations were a threat.

Straight’s national expansion depended on steady recruitments and good PR; their business model was threatened by a growing reputation for “brainwashing.” By the time Dr. DuPont had spoken to the Malcolms in 1981, Straight’s controversy was well known in Florida but had only begun to grow across state lines. The Atlanta facility, the first outside Florida, had opened just 5 days before the Malcolms arrived in St. Petersburg; the Cincinnati facility opened a few months later, in January, 1982.

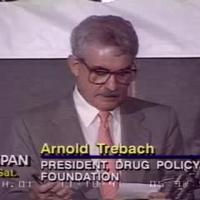

Straight’s facility in Cincinnati, OH

On April 3, 1982, the Cincinnati Enquirer published an article about the Malcolms’ report along with an article about an investigation from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) into complaints of “coercion and brainwashing.” A third article in the Enquirer, also run that day, featured assuring statements by Jerry Rushing, Cincinnati Straight’s director – “he understands how people can conclude there’s brainwashing going on ‘because the kids change so drastically'” – and the statements by a satisfied client who countered the accusations of brainwashing:

“I was more brainwashed when I was on drugs than when I was in Straight. It’s not brainwashing here, it’s people helping people. They have the tools here to help people, and it’s up to the individual to change.” Complaints of coercion and brainwashing by Straight Inc., a three-month-old drug rehabilitation program in Clermont County, might prompt a state investigation. The Cincinnati chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which is investigating the complaints, has not taken legal action so far. But Jonathon Schiff, a ACLU co-operating attorney, related the complaints in a letter in mid-March to the Ohio Bureau of Drug Abuse and asked for an investigation of the program, which treats people aged 12 to 21. Does Straight brainwash kids? Is it a cult? Does it have a religious overtone? Are teens’ constitutional rights violated? In a 31-page report, the Malcolm’s cleared Straight of all these charges but recommended several areas for improvement and safeguards. They labeled Straight a “phenomenal” program that accomplishes what it intends.

While state authorities investigated the Cincinnati program, Ronald Reagan’s Drug Policy Advisor, Carlton Turner, attended one of Straight’s fundraising banquets in Florida, publicly praising the franchise to all in attendance, including the Florida State Attorney General, Jim Smith, and several state representatives.

Check back next week for Part 4. Chatfield’s series will run every Thursday.