“The Drug Store of the Future”: Prohibition and Medicalization

- Emily Dufton

- May 27, 2014

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2023

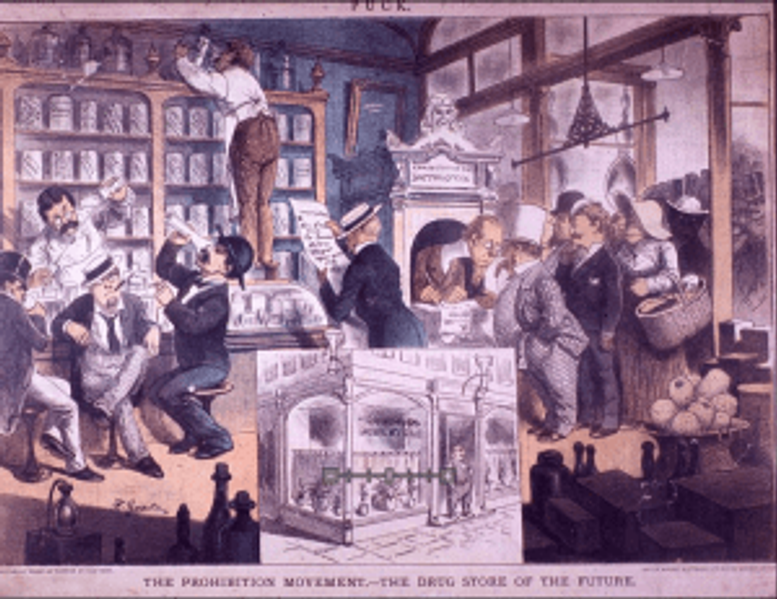

A few weeks ago I had spent a couple of hours surfing the National Institute of Health’s fascinating online library, Images of the History of Medicine (IHM). There I came across an image that surprised me with how relevant its message about prohibition and the subsequent medicalization of banned substances was, even now, 132 years after it first debuted.

This image, “The Drug Store of the Future,” was first published in Puck magazine on September 20, 1882 – 38 years before federal Prohibition was the law of the land. And yet it tells a story that may seem familiar to those who have studied other movements that have sought to prohibit or legalize certain drugs.

In this illustration, a long line of men (and two visible women) wait to be seen at a “Doctor’s Office” (which is really no more than a small vestibule next to the bar), where a long-necked physician is peering at a man’s tongue while scribbling something onto a scroll. The man before him studies his “prescription,” which is little more than a cocktail recipe, while two “pharmacists” in white shirtsleeves and aprons gather the necessary supplies. Ingredients – including rye whiskey, bourbon, brandy and, for some reason, no fewer than three cans of cloves – line the clean and orderly shelves, while three other “patients” sit at the bar, “medicating” themselves with their drinks. Then, in order to make sure the message is clear, a graphic insert shows a man standing at the exterior of the room, where “Saloon” has been crossed out and “Drug Store” has been written underneath.

Satire? Sure – this appeared in Puck after all, the National Lampoon of the late 19th century – but, at its core, all great satire reveals certain elements of truth. And the illustrator working for Puck in 1882 knew that, should the United States ever try to outlaw alcohol, clever doctors and patients would find a way to medicalize its use.

A similar, if significantly less satirical, argument was made in the 1990s when the nation’s first medical marijuana laws were passed. Sue Rusche, founder of National Families in Action and a leading activist in the parent movement, argued in her 1997 book Guide to the Drug Legalization Movement and How You Can Stop It! that “medical marijuana” was little more than a ruse, “a first step to full legalization” of the drug. Rusche had been fighting Keith Stroup and his organization NORML (the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws) for years, arguing that NORML’s support for medical marijuana was little more than a “red herring to give marijuana a good name.” Rusche particularly feared that the results of this tactic would be decreasing attention on the drug’s dangers and increasing focus on what Rusche thought were its overblown medical benefits. In her Guide, Rusche was not wholly unsympathetic to the idea that certain elements of cannabis did help the suffering sick, but she preferred the use of the legal, FDA-approved drug Marinol (which contains dronabinol, a synthetic form of THC) instead. As for the use of straight weed, Rusche condemned Stroup for lobbying for a drug that “the FDA has not approved as safe or effective for any use in medicine.”

Rusche was particularly upset by how Stroup and decriminalization supporters “shamelessly exploited the sick and dying” to prop up their argument. Rusche wondered if medical marijuana supporters were actually seeking “compassion or profit,” and argued that head shops and buyers’ clubs – which Rusche claimed targeted children and had lain dormant during the Reagan era of “Just Say No” – often sprouted in legalization’s wake. She concluded that most medical marijuana supporters were hardly as benevolent as they seemed: “Many who are advocating drug legalization appear to be motivated by something other than concern for seriously and terminally ill people, public health, or the well-being of children and adolescents.”

Rusche’s conclusions are not terribly dissimilar to what the illustrator at Puck was getting at in 1882: that when an illegal drug is turned into medicine, it can (and will) reach “patients” who aren’t actually all that sick. But whereas Puck was mocking the idea that a formerly-legal drug will still be consumed, under a medical guise, when prohibition is the order of the day, Rusche was concerned that medicalizing an already-illegal drug will turn illicit drug use into a medical masquerade, and that this ruse could fool voters into supporting full legalization. Most interestingly, her 17-year-old concerns are still being voiced today. As 58% of Americans now support legalizing medical marijuana and New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Florida, and even some states in the Deep South consider passing their own medical marijuana laws, some public leaders, like Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey, are voicing very parent movement-inspired complaints.

“See, this is what happens,” the governor said at a news conference in December 2013. “Every time you sign one expansion, then the advocates will come back and ask for another one… Here’s what the advocates want: they want legalization of marijuana in New Jersey. It will not happen on my watch, ever. I am done expanding the medical marijuana program under any circumstances. So we’re done.”

One can only imagine what a clever illustrator at Puck (had the magazine not shut down in 1918) could have done with that.