Texas Veterans for Medical Marijuana: Backstory on a “War Without End”

- Claire Clark

- Jun 24, 2014

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Last week, I attended a panel discussion co-hosted by Texas Monthly and the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University. The subject for debate was a recent article by Bill Martin, the director of the Institute’s Drug Policy Program. “War Without End,” published in the June edition of Texas Monthly, describes how Texas veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are successfully self-medicating for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with marijuana. (Trigger warning: their stories are not easy reading). The decision to opt for cannabis over the antidepressants, sleeping pills, or psychotropic medications commonly prescribed by Veterans Administration (VA) doctors makes these veterans criminals in the state of Texas. Although Governor Rick Perry recently said he plans to “implement policies that start us toward decriminalization,” the Texas Legislature hasn’t budged in recent years. Unlike Colorado or Washington, Texas does not have a ballot initiative or referendum process, so the Legislature is the state’s main route to reform. Majority support from the public and the best efforts of groups like the Marijuana Policy Project and local chapters of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) have, so far, come to naught.

Enter the veterans. Reformers believe Texas legislators will listen to war heroes, and state Senator Joan Huffman (R-Houston), a panelist at the Baker Institute event, seems to agree. Huffman told audience members that, in her opinion, a focused campaign for medical marijuana legislation for veterans diagnosed with PTSD would stand a better chance of success than broader initiatives aimed at population-wide medicalization, decriminalization, or legalization.

Photo illustration by Darren Braun for Texas Monthly

“When a guy has done four tours in Iraq, like some of our people, and been wounded in action, it’s hard to look him in the eye and call him a slacker pothead,” one veteran and activist told Texas Monthly. This new depiction of the traumatized veteran as uniquely deserving of marijuana does more than challenge the stoner stereotype. It recalls many of the psychological, symbolic, and treatment policy developments associated with the Iraq War’s most frequently cited historical analogue: the war in Vietnam.

As Martin’s article notes, the diagnostic category of PTSD is itself a byproduct of the Vietnam War. The notion of war-related psychological trauma, as expressed in insomnia, flashbacks, panic attacks, paranoia, alienation, and incapacitating depression, is not new. But its manifestation as PTSD in the 1970s was “inextricably connected to the lives of American veterans of the Vietnam War, with their experiences as combatants and, later, as patients of the Veterans Administration Medical System,” writes anthropologist Allan Young in his masterful history of the topic. When the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III) was under development in the mid-1970s, psychiatrists such as Robert Lifton and Chaim Shatan lobbied for the creation of a subcommittee to study “post-Vietnam syndrome.” They ultimately formalized a working group to study a less politically charged concept called “post-combat disorder,” and the project soon expanded to include research on stressful events unrelated to combat.

But the veteran remained the focus of popular and psychiatric concern. By the early 1970s, writes Young, the “crazy Vietnam vet”— a young man prone to drug abuse, rages, and suicide attempts— had already become an “American archetype.” The PTSD diagnosis helped explain the troubling depictions of unstable American servicemen that regularly appeared in press, television and film.

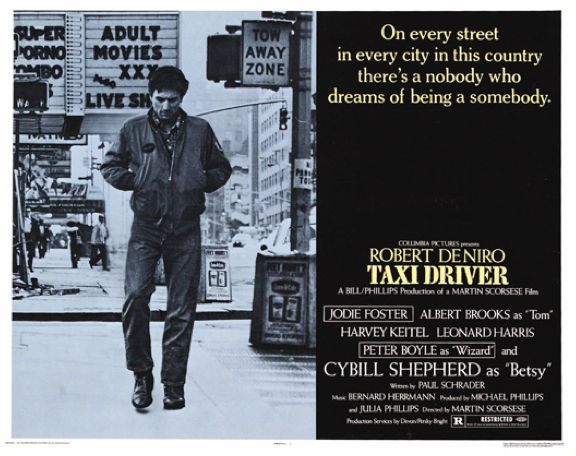

Taxi Driver (Directed by Martin Scorsese; Columbia, 1976) features Robert DeNiro as the now-iconic disturbed Vietnam veteran, Travis Bickle

The crazy vet archetype, historian Jeremy Kuzmarov argues, also fit into a larger fable: The Myth of the Addicted Army. Kuzmarov contends that both conservative politicians and antiwar activists exaggerated the scope of drug use and rates of addiction among US troops in Vietnam. Conservatives argued that the counterculture had infiltrated the conscripted forces (a point which, historian Michael Kramer has recently shown, was not entirely baseless). Drugs, especially marijuana, functioned as a symbol of countercultural resistance and recreation.

Photographer Tim Page (CORBIS, 1968). Image analyzed in Michael Kramer’s Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (OUP, 2013)

According to Kuzmarov’s primary sources, servicemen also viewed illicit drug use as a form of self-medication. Although psychiatrist Edward Khantzian did not fully articulate his self-medication hypothesis until 1985, 37 percent of drug-using soldiers in Vietnam reported that they used substances to “forget the killing and relieve the pressure” of combat. The influential study of heroin-using Vietnam veterans led by Lee Robins showed that fewer than 10 percent of detoxified soldiers resumed their heroin use immediately after returning home. The high remission rate bolstered the theory that most soldiers’ heroin use was a coping mechanism adopted in response to an exceptionally stressful environment— not a form of social protest, a moral failing, or an irreversible medical disorder.

Soldiers who did relapse after they arrived back in the States were greeted with a host of new addiction treatment services, both inside and outside of the VA. Under the direction of advisor Jerome Jaffe, the Nixon administration scaled up two emerging models for heroin addiction treatment, methadone maintenance and therapeutic communities. In both types of programs, marijuana use was more likely to be viewed as an infraction than a therapeutic aid.

Confrontational group therapy and methadone treatment for veterans. Life photoessay, Arthur Schatz, July 1971

Although some drug treatment programs began experimenting with controlled drinking in the 1970s, there was no mainstream justification for teaching people in treatment to learn to smoke marijuana “socially.” Marijuana had a questionable legal and medical status; its apparent risks to initiates and recovering addicts were supported by academic theories that cannabis serves as a “stepping stone” or “gateway” to harder drug use.

In contrast, Baker Institute panelist, NORML representative, and retired Major David Bass said cannabis was not a “gateway drug”; it was an “exit” out of addiction to the prescription painkillers and psychiatric medications prescribed to him by VA doctors. Fellow panelist Dr. Neeraj Shah of Seton Medical Center in Austin marshaled scientific research that supported Bass’s story. In states with medical marijuana laws, veterans with PTSD can access cannabis through the VA, and researchers can study its effects; in states like Texas, a positive drug test for marijuana could send a self-medicating veteran to a traditional rehabilitation center— and back to the pharmaceutical regimen that originally exacerbated his problem.

Shah argued in favor of making medical marijuana available next year for patients like Bass, the “severest patients who are committing suicide from not just PTSD but also chronic pain and other end-stage debilitating disorders.” Since the 1970s, PTSD has morphed from a politicized response to a controversial war to an relatively uncontested medical diagnosis; in more than twenty states, marijuana “self-medication” is now just “medication.”

Even so, recent debates in Texas and beyond have shown that the drug remains a potent symbol of social deviance– and I don’t believe politicians have yet devised a viable exit strategy for the culture wars.