Teaching Points: Opium, Empire, and State in Asia

- Bruce Erickson

- Aug 2, 2016

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Today’s post is from Dr. Bruce Erickson. He is currently the chair of the department of history at LeMoyne College in Syracuse, NY.

In recent years I have included in my rotation two courses that begin with the narcotics trade, “Coca, Culture, and Politics in Latin America” and “Opium, Empire, and State in Asia.” These two classes began life as one that tried to combine “Wars on Drugs” with Wars of Drugs,” so really they were and are less about drugs themselves than about the politics of drugs. Or better, they use the study of narcotics to explore larger histories. In their conception my classes are simply a commodity chain approach to studying and teaching history. What differentiates coca, opium, and their derivatives from other commodities goes beyond their effects to their inconsistent and shifting legal status, the social consequences of their introduction, and their social, political, and economic importance at particular times and places.

Bruce Erickson, Trafficker in History

Given the brevity of this post I will confine most of my discussion to “Opium, Empire, and State in Asia.” As the title suggests, the course revolves around the age of colonial empires and the emergence of modern independent states. Although Turkey and Iran have their own histories with opium, the primary focus is on South, Southeast, and East Asia, or from India to Japan.

The British opium trade and the Opium Wars are familiar to most. In the familiar narrative, the British began to trade in opium as a solution to their “silver problem,” which was created by British demand for Chinese tea. That simple statement requires a discussion of British and global production and trade patterns, the emergence of “addictive consumables” as important commodities in European societies (their role in the industrial revolution, in the development of the middle class, and more), how Spanish colonial silver contributed to shaping the British-Asian trade and the Chinese economy… The questions go on and on, and are just an example of how opium acts as a gateway to the study of much larger histories.

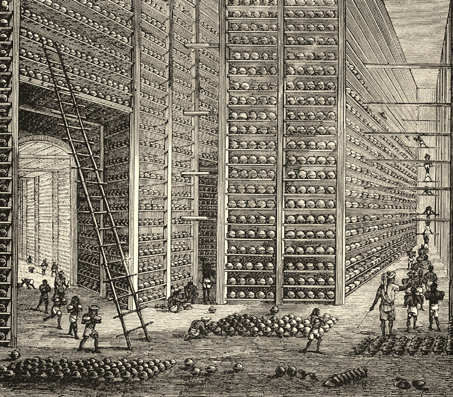

The Gateway to History: A Stacking Room in India

To go further, Britain did not create the European opium “habit,” it adopted it from Portuguese and Dutch traders in the Indian Ocean. British expansion of the opium trade only goes along with the development of its empire beyond those of its predecessors. Carl Trocki argues that without opium there would have been no nineteenth-century British Empire. Few students can accept that the British Empire was not inevitable, but even raising the question forces them to think more deeply about what the empire was and how it was constructed.

Narcotics do more than just provide a window through which to see certain histories though. They also serve as a connection between eras, between colonialism, post-colonial state building, the unconventional warfare of the Cold War era, and the contemporary age of “Wars on Terror.” Once opium was established in East and Southeast Asia it remained as a vexing problem and an exploitable resource, often at the same time, for Asian states, insurgents, and intruders. For a century after the Opium Wars Chinese leaders had to control opium in order to govern but also needed the wealth it represented to compete for power. Consequently, an exploration of Chinese, and Japanese, politics and conflict can easily revolve around opium. Likewise, the opium monopoly in Southeast Asia was a key resource for colonial states and, later, opium profits supported Westerners and their clients, and sometimes their adversaries as well. From the eighteenth century to the twenty-first the center of global opium production followed Western ambitions from China to Southeast Asia to Afghanistan. As teachers we search for narratives to organize our topics. Opium provides this narrative structure across disciplinary and political boundaries alike.

Of course, the histories and social and political relations of coca and opium differ significantly. Perhaps most notably for my purposes the coca leaf is still embedded in indigenous Andean culture while opium’s explicit connection to religion long ago disappeared. For that reason, “Coca, Culture, and Politics in Latin America” necessarily leads into questions of how we define “drugs,” what differentiates culturally significant psychoactive substances from western narcotics – and why political and legal conventions privilege the latter in setting national and international law. There are consistencies between coca, legal stimulants, and opium as well. Few, outside of specialists, know that coca fueled the Andean silver economy before its caffeinated cousins (perhaps) sparked the industrial revolution in Europe. Like opium, coca and its derivatives have been used to fund insurgencies and governments alike, and, like opium, they often travel the same routes as insurgents, guns, and political influence.

We know he’s looking for the lab

Teaching history through drugs has its positives and negatives. On the plus side, many students who have little or no interest in history are drawn in by what I call the “giggle factor.” No matter how the subject is broached students react as if drugs are somehow funny – a colleague tells of discussing heroin abuse among jazz musicians and having students titter at the mention though he is talking about overdose deaths and ruined lives. Many find it easier to think history if they can begin with the “funny” subject of drugs. The negative side of focusing on narcotics is that some have difficulty getting beyond them. Some, who I refer to as “Whoa dude” students, think we are going to spend fifteen weeks talking about getting high (“When’s the lab?”). The complexity of the course comes as quite a shock to them. Others are more serious, but because we enter our studies with the narcotics trade they assume that the narcotics trade is the only dynamic that made, or makes, the world go around. Both of my drug courses are interdisciplinary. They serve the College Core requirement for an interdisciplinary science or social science and are, or have been, cross-listed by the Political Science and Peace and Global Studies programs. Finally, being the substance guy on campus has led me in another direction that I never imagined. A few years ago a biochemist colleague began to consult with me about an idea for a course about caffeine in the brain and in history. Last fall we debuted a team-taught interdisciplinary science course, “Chemical Science 342: Bitter/Sweet: Stimulating Human History with Caffeine and Sugar.” We feel like it is a work in progress as we continue to conceptualize how to combine our very different fields into one coherent whole that students who major in neither can comprehend. For me, all these substances, legal or otherwise, are gateway drugs through which to approach history and society. I am the academic pusher, offering a free dose only to lure the unsuspecting student into a (downward?) spiral of intellectual inquiry.