Review of A Drunkard’s Defense

- Michael Brownrigg

- May 4, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2023

Editor’s Note: Today’s post comes from contributing editor Michael Brownrigg. Michael recently received his PhD in US history from Northwestern University, where he studied the relationship between emotion, white masculinity, and capitalism to explain the emergence of an antinarcotic consensus in America at the turn of the twentieth century.

In A Drunkard’s Defense: Alcohol, Murder, and Medical Jurisprudence in Nineteenth-Century America (University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), Michele Rotunda has written a significant contribution about the history of alcohol consumption that will appeal to students of numerous fields, most notably scholars engaged in legal, medical, and cultural studies. Drawing from an impressive array of primary sources, Rotunda’s taut narrative, tracing the complex evolution of juridical precedents beginning in the colonial era that established the culpability of defendants accused of often gruesome crimes while intoxicated, is revelatory.

Rotunda’s extensive use of court documents, in particular, illuminates in exquisite detail the highly contested nature of judicial concepts like intention and responsibility, and how they considerably influenced verdicts in cases of alcohol-induced criminality. Did murder commissioned under the influence of alcohol constitute a deliberate, voluntary, and premeditated crime? If not, was the accused nevertheless at fault for willfully partaking in a vice that could disorder the mind and facilitate the perpetration of murder—an idea resting on deeply entrenched beliefs in American society about the immorality of drunken indulgence that knowingly caused mental derangement? Or, as physicians who were increasingly concerned with the physiology and psychology of intoxication proclaimed, was the impetus for murderous behavior exhibited by defendants vastly more complicated, requiring nuanced diagnoses that only practitioners’ scientific expertise and empiricism could provide?

“The Drunkard’s Progress; From First Glass to the Grave” Currier & Ives print, c. 1846. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

A Drunkard’s Defense pointedly addresses these questions by cogently elucidating how ideas regarding morality and how cultural assumptions about gender, class, and race infiltrated the fields of medicine, science, and law. According to Rotunda, this intellectual, moral, and social overlap led to a proliferation of competing interpretations that engendered a remarkably convoluted—and ultimately unsettled—attempt to reform the arbitrary nature of assigning blame and meting out excessive punishment.

Because of the porosity of these disparate fields, Rotunda argues, social attitudes regarding the perniciousness of alcohol—opinions influenced by ubiquitous temperance narratives that depicted drunkenness as inimical to the vaunted domestic ideal—prevented the emergence of consistent precedents free from cultural bias for the judicious and equitable consideration of extenuating circumstances and medical assessments while determining culpability for murders committed in a drunken state. As Rotunda shows, the legal concepts of intent and responsibility were astonishingly elastic, and the meaning applied to these ideas was largely dependent on who possessed the professional or cultural and moral authority to define them.

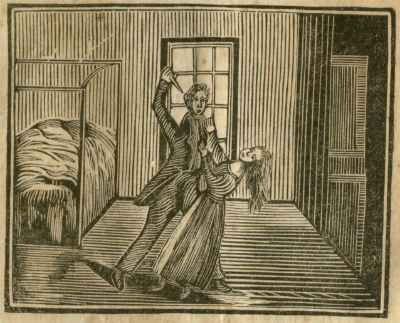

Engraving from Trial, Sentence and Execution of Joel Clough (1833) showing “Clough stabbing Mrs. Hamilton, as described by witnesses”. A Drunkard’s Defense discusses this trial in chapter 2. Image from Yale University Law Library.

A Drunkard’s Defense examines these power struggles to illustrate ambiguities surrounding the concept of inebriety. Adding another dimension to the drama of nineteenth-century legal cases, America’s burgeoning print culture graphically chronicled to an enthralled reading public the courtroom spectacles accompanying heinous murders. Rotunda explores the historical implications of these epistemological battles by explaining how judges, jurors, medical practitioners, and even ordinary Americans vigorously competed to control the knowledge used to decide the fate of defendants claiming temporary insanity as a result of intoxication for mitigative or possibly exculpatory purposes.

Rotunda fascinatingly explicates the complex, uneven historical trajectory of the law’s attempts to establish the judicial, intellectual, and diagnostic distinctions employed to ascertain guilt. Beginning in the 1820s, medical theorists developed and refined the concept of delirium tremens, a diagnostic distinction that considerably complicated the enshrined maxim that “drunkenness is no excuse” for criminality that had long served as the predominant legal precedent for determining guilt. The concept of delirium tremens, according to Rotunda, effectively medicalized the condition of inebriety by classifying the uncontrollable urge to drink as a disease rather than simply a vice.

Since delirium tremens was perceived as a medical pathology impairing the capacity for reason caused by the sudden absence of drink, the condition imparted legitimacy to defendants’ claims of temporary insanity even for murders committed when not under the influence of alcohol. Jurors deliberating the distinction between active intoxication and the “settled insanity” caused by delirium tremens then weighed evidence provided by character witnesses attesting to the moral rectitude and virtuous character of defendants who, despite refraining from alcohol, suffered from an affliction that precluded the possibility of criminal intent and responsibility. As Rotunda suggests, the formulation of delirium tremens as a disease helped garner the prestige and status that medical experts sought for the field of medical jurisprudence as a venue for further professionalizing the discipline.

In addition to the interventions of medical authorities in the courtroom, Rotunda shows that culture played a crucial role in legitimizing temporary insanity as a viable defense to mitigate capital punishment. Rotunda notes the contradictory nature of the temperance narratives that immersed juries and judges in sensational stories of lurid and gruesome behavior that supposedly threatened the moral foundations of American society. According to Rotunda:

Temperance advocates professed that the decision to drink was a voluntary sinful act, yet both their descriptions of drunkards’ lives spinning out of control and their resistance to try to reform actual drunkards suggested a limit to free will if not individual moral responsibility. Moral reformers could and did condemn the drunkard for the initial decision to drink even as they acknowledged one might no longer have the power to resist the urge (p. 40).

Title page of A Full Report of the The Trial of Orrin Woodford for the Murder of His Wife. A Drunkard’s Defense discusses this trial in chapter 3. Image from Google Books.

In other words, temperance narratives emphasized that drink was a perniciously seductive threat and that anyone who took that first sip could suffer a precipitous descent into depravity. The conventions of temperance rhetoric often emphasized the “transformative role of alcohol on an individual’s character… demonstrat[ing] the power and influence of alcohol in causing a man” to commit heinous crimes (p. 44). Furthermore, Rotunda points to prevailing public sentiment that “Demon Rum” and its purveyors were complicit in inducing states of drunken rage in individuals who could not resist the allure of alcohol. “Somewhat ironically,” she writes, “the demonization of alcohol and those who sold it allowed for a narrative that mitigated the actions of the drunkard himself” (p. 60).

When combined with an incisive analysis of the emotional and remorseful narratives of members of the Washingtonian Abstinence Movement that documented their involuntary deviance caused by the irresistible impulse to drink and their eventual triumph over their “enslaver,” Rotunda convincingly demonstrates that a potent argument emerged in the mid-nineteenth century that challenged ingrained juridical notions of intent and personal responsibility.

Yet, despite these dramatic alterations in the prosecution of criminal drunkards, an equally dramatic development occurred in response to the development of the concept of “moral insanity” in psychiatric discourses. In the latter half of the century, proponents of moral insanity argued that inebriety caused not only intellectual or psychological defects distorting judgement but also impaired the drinker’s moral and emotional faculties. The sheer malleability of moral insanity enraged many in the medical profession who saw the doctrine as an embarrassment that undermined the authority of the discipline and exposed it to attacks from detractors challenging its empirical validity.

The belief that moral insanity was far too scientifically imprecise to explain individual deviations or pathologies was particularly disconcerting to many doctors, who thus thought the idea essentially could be employed to absolve defendants of any responsibility for their misconduct. Rotunda refers to this stark reversal as a “backlash” that invited public ridicule and threatened to discredit the medical profession now riven by disagreement and intradisciplinary hostility and factionalism (p. 155).

After nearly a century of attempts to reform the judicial system to better reflect the medicalization of inebriety as a disease for mitigating charges levied unfairly against defendants accused of crimes committed while intoxicated, the medical profession largely abandoned its medical jurisprudence aspirations by the late nineteenth century. This retreat had severe consequences for legal reforms regarding intoxication and criminal activity that reverberate to the present.

Despite the many merits of Rotunda’s book, I was struck by an insufficient engagement with The Journal of Inebriety, a publication where numerous medical theorists debated the complex relationship between intoxication, criminality, and responsibility. This omission was surprising given Rotunda’s discussion of Journal Editor T. D. Crothers’ ideas about the medico-legal implications of inebriety.

It might also have been interesting for Rotunda to examine how other forms of inebriety were addressed in judicial settings. How, for example, did courts treat morphine addicts charged with crimes committed while intoxicated. Crothers, for one, was deeply concerned with the culpability of “morphinomaniacs.” In language similar to the kind he used to describe the moral impairment of drunkards, he alleged that morphine addicts were afflicted with a double consciousness that incapacitated their ability to discern objective relations, and he questioned their capacity to act as rational individuals responsible for their actions. Finally, Dr. Leslie E. Keeley and his turn-of-the-twentieth century advocacy that drunkenness was a disease is glaringly absent from the narrative.

Despite these reservations, Rotunda’s compelling and engrossing history fills a gap in the historiography of alcohol addiction. A Drunkard’s Defense should be considered an invaluable contribution to the field, and one that I’ll revisit frequently.

Michele Rotunda, A Drunkard’s Defense: Alcohol, Murder, and Medical Jurisprudence in the Nineteenth Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021); 216 pp; 9 b & w ill.; ISBN: 9781625345547; paper; $28.95; https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1gt948x.