Editor’s Note: Today’s post in honor of Black History Month comes from contributing editor Sarah Brady Siff, a visiting assistant professor at the Moritz College of Law at The Ohio State University, in affiliation with the Drug Enforcement and Policy Center (DEPC).

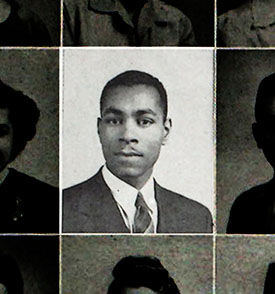

Samuel Carter McMorris in the Makio, Ohio State University’s yearbook, in 1944.

In 1962, the United States Supreme Court struck down California’s “narcotics addict” law in the case Robinson v. California. Samuel Carter McMorris, the lawyer who argued and won the case, was a fierce criminal defense lawyer for the Black community in Los Angeles during a tumultuous era. Robinson was the second of two criminal cases McMorris successfully appealed to the Supreme Court, both of them at his own expense on behalf of indigent clients. Yet McMorris has been lost to history, left without so much as a Wikipedia page.

As McMorris knew, abuse was inherent in California’s narcotics addict law. A quarter of drug arrests in Los Angeles during the 1950s and early 1960s were solely for the crime of addiction, a charge that did not even require the physical presence of drugs themselves. The testimony of an officer that he had observed injection marks on the arm of a suspect was ordinarily enough evidence for a conviction. Police freely and frequently demanded that citizens roll up their sleeves and expose the insides of their arms so officers could inspect for needle marks. This “evidence” was so conclusive in court that suspects in custody sometimes disfigured themselves by burning the area with lit cigarettes. McMorris’s legal activism helped overturn the criminalization of addiction and this type of invasive drug enforcement.

Early Life

McMorris was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1920. His father, Arthur, was a policeman, and his mother, Marie, was a homemaker; Samuel had four younger sisters. When he graduated from East High School in 1937, his class named him both “most industrious” and “most conscientious.” He worked as a traveling salesman, served in the Army, then attended Ohio State University, where he attained a law degree in 1950.

Pictured in 1950 with the staff of the Ohio State Law Journal, Samuel Carter McMorris was the first Black student to serve in that role.

McMorris moved to Los Angeles in 1951 and took a job with LA County, first as a social case worker and then as deputy marshall to the municipal court. He passed the California bar exam in 1953 and resigned from public service, opening his own practice downtown. The following year, he joined the law firm of Gordon and Schaffer.

Robinson v. California

During the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights violations by LAPD officers were a continuous, brutal reality in Black and Mexican-American neighborhoods. Arrests and convictions for drug crimes rose sharply as policemen targeted and harassed non-white residents. Highly discretionary enforcement and the probative nature of drug evidence rendered drug laws—particularly the state’s narcotics addict law—extraordinarily useful for the unspoken but ever-present goal of enforcing the racial status quo.

Police check suspects’ arms for signs of needle injection indicating heroin or morphine use in these news photographs from 1953, 1957, and 1960. Robinson v. California prevented police from arresting drug suspects who were not in possession of drugs or under the influence of drugs.

McMorris had previously defended several clients charged with addiction before taking the case of Walter Lawrence Robinson, who had been arrested and convicted in 1961 under California’s law that made it a misdemeanor “to be addicted to the use of narcotics.” The case reached the Supreme Court the following year, and the court found that the law was in conflict with the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishments.” McMorris told a reporter that he had long been concerned about the constitutionality of this law and that he had been building his argument against it for several years. McMorris really was, as his high school classmates had noted, industrious and conscientious.

Asked why he had spent several thousand dollars of his own money to litigate the case (as well as Lambert v. California in 1957), McMorris replied, “As a Negro myself, I am naturally interested in the rights of minorities, generally. I am interested in those whose rights are often forfeited through lack of proper legal aid. And beyond that, I believe that when one man loses a right, that right is lost to all men.”

I plan to present the legal details and drug-enforcement milieu of the fascinating Robinson case in greater detail elsewhere (with citations). Certainly it was an important element in a whole cascade of federal judicial intervention related to the unconstitutional enforcement of state and local drug laws in postwar California.

Fight Against Police Brutality

But in looking specifically at McMorris’s life in the sources at hand—most notably the recently digitized Los Angeles Black newspaper, the California Eagle—what I notice most is McMorris’s clear and persistent opposition to police brutality. He proved willing time and again to confront Los Angeles police over their enforcement behavior, both in the courtroom and in highly critical public statements aimed at law enforcement leadership.

From the front page of the California Eagle, December 19, 1957

In 1955, McMorris won acquittal for Cora Lee Anderson, who had been arrested along with eight other people for vagrancy and for “offering” (prostitution). During the trial, the Eagle reported:

“McMorris emphasized the fact that the officers, one of whom later shot another woman whom they arrested for offering, had been drinking in neighborhood taverns all night, and questioned whether the jury was willing to incriminate the defendant for the rest of her life on the sole testimony of a drunken police officer.”

Anderson, McMorris said, was in court “fighting against police brutality and injustice, fighting for her womanhood.”

In Lambert v. California—McMorris’s successful 1957 Supreme Court challenge to a Los Angeles law requiring anyone with a felony conviction to register with the chief of police—he presented numerous details about police misconduct toward his client, Virginia Lambert. LAPD, according to McMorris, had conducted a warrantless search of her purse on the street and had also forced her to roll up her sleeves and expose her arms for needle marks. During a post-arrest examination at the station house, an officer also searched “the inner parts of her person, apparently searching for narcotics, though there’s no showing that he had any information relative thereto.” After winning on appeal, McMorris told a reporter that the registration ordinance had long “served as a vehicle for police brutality.”

In another 1957 case for Virginia Lambert, McMorris successfully appealed a superior court ruling that an LA shoe store could legally refuse service to Black customers. The ruling was the first of its kind in the United States, he told reporters afterward.

Samuel Carter McMorris represented Ora Nelson in a $50,000 suit against the Los Angeles Police Department after officers stomped on and broke her foot. The California Eagle covered her story and printed this photograph.

McMorris routinely tried to hold the LAPD accountable for its brutality against Black Angelenos. In 1958, he defended James Cooper, a disabled Korean War veteran beaten by five LAPD officers. Cooper had refused to serve as a witness to a traffic accident despite police threats to arrest him on a false charge of public drunkenness. The next year, plainclothes narcotics officers forced their way into the home of 58-year-old Ora Nelson and broke her foot. Nelson, described as a pillar of the Baptist Church in Compton, engaged McMorris to file suit against the police department for $50,000 in damages.

In the summer of 1961—the same year he successfully argued Robinson v. California at the Supreme Court—McMorris moved to Sacramento and opened a law practice. He continued to see police brutality as an important civil rights issue. After civil disorder consumed LA’s Watts neighborhood in 1965, he wrote:

“[T]he majority of Americans refuse to acknowledge that the motivating cause of the uprising was the failure of law enforcement to offer protection while at the same time it persistently visited brutality and abuse upon the Black man…. Watts was the extreme reaction to extreme provocation; physical violence met with physical violence.”

In May 1967, McMorris appeared in Sacramento municipal court as counsel for members of the Black Panther Party who had staged an armed protest at the state capitol during an Assembly session about gun control. A core component of Black Panther activism was armed self defense in opposition to police brutality. Outside the courthouse, he told a reporter that his clients’ actions were “essentially a civil rights protest.”

In May 1967, McMorris answered a television reporter’s questions outside the Sacramento municipal court where his clients from the Black Panther Party faced charges. Source: San Francisco State University Bay Television Archive

Legacy

This sketch of Samuel Carter McMorris falls far short of a complete picture. He is a typically complicated historical figure, and his life does not lend itself to a tidy appraisal. He often was involved in messy legal affairs on behalf of family members and friends. He might have been the target of FBI surveillance due to his representation of Black radical clients. He wrote at least two anti-cannabis articles for publications of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, and he conducted what seems like a personal crusade against the tobacco industry. Yet, he also wrote for the radical Liberator magazine and, later, for American Atheist. In 1983, McMorris was disbarred in California for neglecting clients, an action he vigorously opposed but failed to stop.

Despite his years of legal and civil rights activism on behalf of Black Californians, McMorris’s death in 2006 apparently did not merit an obituary. He was buried in the National Cemetery at San Joaquin where his gravestone reads “U.S. Army — In God’s Care.”