Public Relations Language Disguises How Drug Discourse Today Is More Successful

- Brooks Hudson

- Jan 31, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Editor’s Note: Today’s post comes from contributing editor Brooks Hudson, a PhD student in history at Southern Illinois University.

If you’ve followed the opioid issue, you might suspect, based on media reports and statements from policymakers, that we have turned over a new leaf in our attitudes toward drugs and are finally moving in the right direction: today we are “expanding treatment” and abandoning the former “punitive” morality play model. Elite discourse reinforces the perception that we have become more sophisticated, science-based and compassionate to users and those with substance use disorders.

That’s only partially true, but not because powerful institutional actors experienced a change of heart; they had to be dragged kicking and screaming into embracing, if only rhetorically, this new model. If anything, grassroots activists, harm reductionists, health workers and criminal justice advocates on the front lines have waged tireless, and at times seemingly thankless, campaigns to reform our draconian laws, and they have succeeded. (Prime examples of these successes include legalizing cannabis, decriminalizing psilocybin in Denver, and expunging criminal records for marijuana arrests in some states.) Activists also shifted the conversation away from the dehumanizing language used to describe people who use drugs among press and policymakers (“junkie,” “addict,” etc), a language that enabled us to conceive of other people as less than human, making it easy on our collective conscience to confine them to cages. Even now, further incremental baby steps are met with the same hostilities and recitations of the parade of horribles that would be unleashed as they used before.

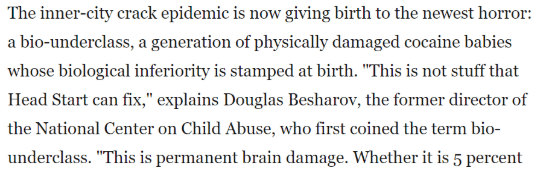

Now, I can anticipate the objection about stagnation and a lack of compassion in prestige. It is true but as a rhetorical matter. Politicians and journalist don’t do the (wink, wink) 1980s racism found in the writings of Charles Krauthammer, who warned readers of the “newest horror: the “crack baby” myth, “a bio-underclass, a generation of physically damaged cocaine babies whose biological inferiority is stamped at birth.”

But that only strengthens my point that, despite the work of activists, the rhetoric around drug users hasn’t really changed. Krauthammer’s vile rhetoric shares more in common with people commenting on phrenology, eugenics, and IQ scores among races on 4Chan today than among say, the Global Commission on Drug Policy panel. But it was outside pressure, not deeply felt conviction of institutional meditations, that resulted in whatever successes we’ve witnessed.

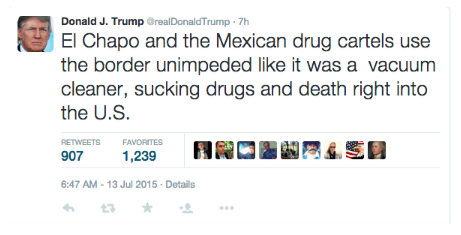

As late as 2005, the New York Times was reviving the “crack baby” myth, but the white-trash version: the “meth orphan.” Of course, because the Times is the paper of record, they did the responsible thing, first snitching on all their rival newspapers and admitting their role in having a harmful impact in the 1980s. It was one of those courageous acts, the kind that takes thirty years to take responsibility for. Their mea culpa is supposed to assure readers that, while they’ve never accurately covered drug-related stories in any decade to date, this time will be different. Today the issue at hand is that rhetoric masks the reality, which is that the same policies remain largely unchanged, but their presentation is different, and that’s the danger. Arguably the one benefit of a Trump administration is that the president is too much of an untrained oaf to know that you aren’t supposed to say the quiet part out loud. He lies all the time, but his presentation is honest.

There are probably hundreds of themes I could’ve selected to show how ideologies in our discourse work, and how they support, rather than confront, the system we have. I selected some pet peeves—though the list is endless: body counts in headlines and the use of phrases like “expanded treatment,” which function as an abracadabra phrase.

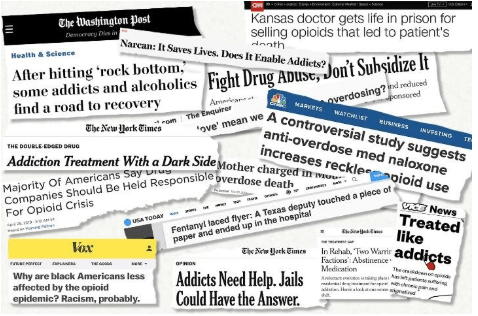

Type in “opioid epidemic” into Google and “death” appears a lot in the findings, as do phrases like “worst crisis in American history.” These things meant to act like quicksand for our attention. Their message? Be scared!—preempting critical thought and favoring emotion. Exploiting fear has a long, storied track record. It has often been successful in convincing citizens to cede to state and corporate actors, who, in exchange, will “solve the problem.” This rarely seems to materialize, however.

Body counts are ideological. Just check press reports about civilian casualties versus deaths of U.S. service members in the Iraq War: U.S. deaths (5,000) are always included, Iraqi civilian casualties (500,000) not so much. It is the lie of omission at issue. Often the author matters more than the number: for instance, this is why when Syrian forces massacred 100 civilians, the U.S. feigned outraged, issuing a blizzard of press releases that harped on longstanding commitments to human rights and all the rest. On the other hand, when a U.S. gunship hit a Doctors Without Borders hospital, it was a regrettable “blunder”—in other words, a big whoopsie-daisy. The “opioid epidemic” has identical dynamics.

From a numbers game, here are stories that should receive double or triple the coverage compared to opioid overdoses: 200,000 to 400,000 preventable deaths because of medical errors, 133,000 deaths attributable to individual levels of poverty, 100,000 deaths related to air pollution, 120,000 excess deaths as a consequence of workplace environment and stress. These stories are underplayed because of money, and because they would require concentrated media conglomerates to attack other concentrated media conglomerates, who are probably advertisers, partners, or perhaps even siblings of the same parent company. Unlike powerless drug users, corporations will wage war with legions of legal minds, where drawn-out legal fights cost millions. There is little appetite for it in media industries with a wide reach. Also, as Matt Taibbi writes in Hate Inc., a long meditation on the current media landscape, fear and drug coverage has been a cash cow for media companies:

“A few sociologists over the years have noted that moral panics benefit the interested players in a particular way. There is symbiosis between big commercial news outlets and state authorities. Scare the crap out of people, and media companies get richer, while state agencies get more and more license for authoritarian crackdowns on the ‘folk devil’ of the moment. A perfect partnership. The crack story exemplified this.

TV stations glamorized the ‘wars’ on the streets, got great ratings, yet rarely got to the heart of what the crack epidemic was: a way for cocaine cartels to expand the consumer base beyond the saturated market of upper-class buyers of powder coke. Crack was just the cartel version of a corporate marketing ploy to rope in poorer consumers.”

Treatment

Everything you read or watch includes the line “expanding access to treatment” as the solution to this crisis. Even the DEA—which I’m sure cares and isn’t just inserting meaningless pablum into print—sprinkles references to “treatment” in its documents for secondary schools. These appeals are disingenuous, cynical, and done in bad faith. The most obvious reason: the phrase is meaningless. Imagine if someone took it seriously: “Okay, great, where do I get that expanded treatment? Is it free? How do I receive medications? Where is the expanded treatment mental health provider?” The answer is, treatment is a language device, not to provide care directly to the people effected but to introduce nice-sounding blather and see if anyone notices.

To see how this phrase is cynical and deployed in bad faith, one can examine obvious things like how only one out of ten people that needs treatment receives it (and an even smaller fraction receives evidence-based treatment); or how the rehab industry is the wild west, filled with con artists creating predatory schemes, preying on vulnerable families, and leaving them to foot bills that sometimes run well into the tens or hundreds thousand dollars for quack remedies such as equine-assisted therapy—a fancy name for hanging out with horses.

From the professional side, only one out of ten doctors have the authority to prescribe medications to treat opioid use disorder. This is a recipe for disaster, and a sign the DEA isn’t serious about evidence-based treatment or lifting a finger to help anyone. A quarter of our incarcerated population also suffers from mental illness, with a majority receiving no treatment at all. Does this strike you as a society that’s dedicated, or even remotely concerned, about the health, safety and well-being of its people? Even within our stratified society, it is hard for affluent families in the middle class with private insurance to gain access to treatment or medication because of blanket prior authorization denials and other administrative roadblocks.

Drug war hawks prefer waging jihad against chemicals rather than acting as advocates for solutions, and not even for pie-in-the-sky theoretical solutions, but ones with working models around the globe. If they wanted to make a dent in the number of overdose deaths, they might consider the European Union, which has a collective population (500 million) greater than the U.S. (330 million), yet it only has about one-tenth of the number of overdose deaths (7,500). What is the difference? These countries have a variation of single-payer health insurance generally available to all citizens; they regulate and cap pharmaceutical prices; and they allow for local experimentation in solutions, including safe injection sites, prescription heroin and morphine for patients that find it effective (at no cost), and investing in social supports that address root causes, like employment and housing, which aid self-improvement. What a shock: states that center the respect and dignity of everyone are more efficacious than those inspired by cruelty and austerity.