Proving Cannabis – A History of Nineteenth Century Medical Marijuana

- Adam Rathge

- Nov 18, 2014

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

“During the month of September, 1862, I took Cannabis on various occasions,” confessed Dr. W. A. D. Pierce in the pages of American Journal of Homoeopathic Materia Medica and Record of Medical Science nearly a decade later. He did so “with the purpose of gaining, through the intoxicating influence of the drug, an insight into the phenomena of Somnambulism, Delirium and Mania, in connection with my researches in Psychology.” Pierce was not alone. Following the formal introduction of cannabis to American medicine in 1840, medical journals were filled with pages and articles recounting the self-administration and experimentation of physicians and their patients. Indeed, while autobiographical accounts of drug use like De Qunicy’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater or Fitz Hugh Ludlow’s The Hasheesh Eater: Being Passages from the Life of a Pythagorean often garner the most attention on the matter, medical doctors were often experimenters themselves – especially when it came to cannabis.

Personal experimentation with cannabis, like this one from Dr. Pierce, was common among physicians in the late nineteenth century.

Like Pierce, most physicians experimented with cannabis for the sake of science and advancing medicine. At the center of this process was the accepted validity of individual experimentation and personal narrative as a form of professional knowledge creation. Dr. John Bell, for example, regularly “engaged in a series of self-experimentations” with cannabis in 1857. In their commentary on his trials, editors at the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal stressed that personal experiments like those from Bell should be “repeated on others equally capable of noting and recording the results.” Nearly fifteen years later, in 1871, Dr. George Miller Beard continued to argue that, “The one and only way by which we can learn the effects of stimulants and narcotics on the human system is by experience; by trying them on a large number of individuals, and observing their effects over a long period of time.”

Many heeded these calls for research. Such experiments, often referred to as provings, continued throughout the late nineteenth century, as demonstrated by a report on a “Proving of Cannabis Indica in Large Dose,” by Dr. Robert C. Bickness in the January 1898 edition of the Therapeutic Gazette. These experiments with cannabis were sometimes driven by curiosity, but were largely driven by a desire to better understand its myriad effects and better utilize liquid extracts of the plant.

Some of what we find in these first-hand accounts of cannabis intoxication by nineteenth century physicians aligns with commonly held perceptions of both recreational and medical marijuana more than a century later. Happiness, contentment, contracted pupils, mental excitement and uncontrollable peals of laughter, were all regularly associated with cannabis. Dr. Pierce, for example, wrote of being “totally absorbed in the music, while a deep subdued happiness, such as I had never before felt, pervaded my whole being.” He also experienced dry mouth and a great feeling of warmth throughout his body. Cannabis was also regularly noted to increase appetite and provide deep and restful sleep, two characteristics that American physicians found beneficial when assessing the potential benefits of cannabis medicines and their potential uses.

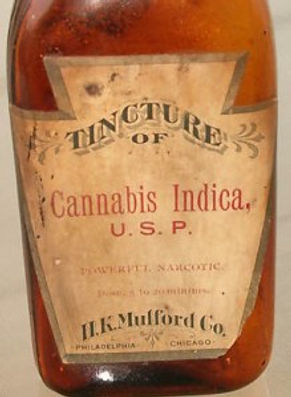

And use it they did. By the 1870s, the United States Dispensatory noted that “the complaints in which it [extract cannabis indica] has been specially recommended are neuralgia, gout, rheumatism, tetanus, hydrophobia, epidemic cholera, convulsions, chorea, hysteria, mental depression, delirium tremens, insanity, and uterine hemorrhage.” Moreover, cannabis preparations were found “to allay spasms, to compose nervous inquietude, and to relieve pains.” This differed “from opium in not diminishing the appetite, checking the secretions, or constipating the bowls.” Such descriptions assure us that cannabis use in the 19th century brought about many of the positive symptoms most often associated with recreational and medicinal use today.

Yet, these personal experiments by American physicians also regularly highlighted a series of frightening symptoms associated with cannabis overdose that often helped temper optimistic expectations and reinforce the potential dangers associated with its use. Distortions of space and time, illusions and hallucinations, erosion of the will, anxiety and racing thoughts, a profound sense of twoness and out of body experiences, and fear of impending death were all symptoms regularly recorded by medical doctors. Dr. Pierce recalled many of these, noting that, “In ordinary health we feel an easy assurance of the power of our will to regulate both the functions of our mind and body; the sudden eradication of this impression is probably the greatest shock the mind can be made to sustain.” Under the influence of cannabis, he found that “this dread[ed] uncertainty in regard to the existence of my surroundings became unbearable; even my own body wore the same appearance and did not seem to belong to me.”

As such warnings spread, many physicians experimented with cannabis only with other doctors around, to care for them and record external observations of these symptoms. As for Pierce, he concluded that “To feel oneself under the influence of Hashish, is to feel oneself in the iron grip of a demon who directs one’s every movement and thought. Alarm, surprise and confusion enthral the reason, while fancy reigns.” Such fears led many physicians to consider cannabis alongside arsenic, chloroform, opium, ether, and other drugs. They could be both helpful and harmful, and therefore their use needed to be restricted by law.

These conflicting accounts of cannabis use are both fascinating and instructive. Medicinal preparations of cannabis proved highly difficult to standardize, leaving physicians unable to ascertain proper doses even with products made by the same company. Inert doses left some physicians feeling let down by the positive therapeutic claims of their peers. On the other hand, particularly potent doses brought about frightening symptoms that also curbed their desire to prescribe medicinal cannabis preparations. This uncertainty was a major reason why cannabis ultimately lost what favor it did have among American physicians in the late nineteenth century. Nevertheless, in today’s debates over legalization and medical marijuana, we most often see only the positive nineteenth century uses on display. And while it is true that physicians regularly recommended cannabis for a wide range of ailments, they did not always do so unequivocally. A more complete picture shows a far more opaque judgement of cannabis, alongside calls for continued research and continued experimentation. Yet, rather than detract from pro-medicalization and/or -legalization arguments, such a history could strengthen this case by demonstrating a clear, historical foundation for such changes – beginning with the re-scheduling of marijuana for medical use.