Points on Blogs: Understanding Society

- Joe Spillane

- Sep 15, 2011

- 3 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2023

There’s plenty of self-promoting, self-referential nonsense out there in the blogosphere. When it came time to thinking about “Points on Blogs,” well…let’s just say that your editor did not feel this feature needed to promote the self-promoting, or add layers of nonsense to the nonsensical. Consequently, we were very pleased to be able to bring to the Points readership the earnest inquiry of the Drugs, Law and Conflict blog and the vivid explorations of the Res Obscura blog. Last time, I promised we’d “go drinking” in this installment, but I’ve decided to “go thinking” instead. Our third blog is Prof. Daniel Little’s Understanding Society, and it moves away from the realm of alcohol and drugs particularly, to the broad questions that animate our investigations. Little is a professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, where he is also currently university chancellor. Here’s how he describes his intellectual orientation on the front page of Understanding Society: “I am a philosopher of social science with a strong interest in China and Southeast Asia. Right now I’m thinking about how to reformulate the philosophy of history in a way that is more closely related to the practice of contemporary historians. I think philosophers need to interact seriously and extensively with working social scientists and historians if they are going to be able to make a useful contribution.”

Crowds cheer for war--understand them?

As for Understanding Society, calling it a blog doesn’t quite capture what Little is trying to accomplish. The recipe for a typical academic blog mixes small amounts of extended analysis with a larger portion of timely reaction pieces, all baked together with heaping pile of whatever comes to mind at the moment. In contrast, here’s Little’s goal, in his own words: “This site addresses a series of topics in the philosophy of social science. What is involved in “understanding society”? The blog is an experiment in thinking, one idea at a time. Look at it as a web-based, dynamic monograph on the philosophy of social science and some foundational issues about the nature of the social world.” Indeed, one can find the entire site organized into a table of contents, or obtain the entire contents through July, 2011 in monograph form (obtained free from the site as a 1234-page[!] pdf file).

Needless to say, that’s a lot to go through. Why should historians of drugs and alcohol care?

We should care because, in the final analysis, we’re all just trying to understand society, working through some of the same basic questions–historical causation, agency and structure, the nature of the state, and so on. Here’s just two quick bits from the blog to give Points readers a sense of what to expect:

The suburbs…

Dependent or independent variable?

In this August, 2011 post, Little discusses the recent edited volume by Kevin Kruse and Thomas Sugrue, The New Suburban History. The post gives a nice overview of what they’re up to (particularly giving them all appropriate credit for exploring the diversity of suburban development and experience), but it also challenges historians and social scientists to push their analysis of the suburbs further. In particular, Little argues, “what the volume doesn’t even try to do is to get at the sociological dynamics that this form of residence, work, and socialization created”–in other words, to look at the suburbs as the dependent variable, not just having been produced, but producing particular forms of social activity and organization. I think some historians, including contributors to the Kruse/Sugrue volume actually have begun to do so, but Little is certainly correct in characterizing this as an important frontier for continued work.

Social networks…

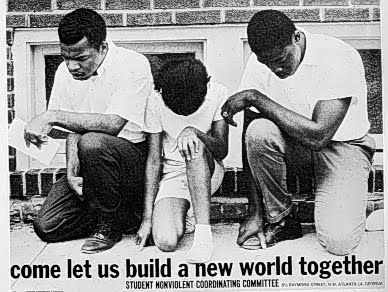

The real social network

Those of you who listed to my keynote address at the Buffalo meeting will, I’m sure, gladly forgo more discussion from me as to why social networks matter for historians, particularly when Understanding Society offers up such an extended and rich exploration of the same subject. Find the entries with a “social network” label, and you’ll find a solid week’s worth of reading, including “Are Social Networks Fundamental?” (from November, 2009), which makes great use of Doug McAdam’s work on social movements and network analysis.

There’s much more than this, particularly on the philosophy of history–Little published New Contributions to the Philosophy of History just last year (Springer, 2010)–which historians should find engaging and worthwhile.