Editor’s Note: Today’s post comes from contributing editor Bob Beach, our resident New Yorker who provides insights into the his state’s twisted path to potential cannabis legalization. Beach is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Albany, SUNY.

On August 28, 2019, New York State officially decriminalized marijuana. Most saw decriminalization as an important step toward the even more equitable legalization measure that failed to pass the Democrat-led state legislature this year, but which seems inevitable given recent trends in legalizing (with the recent addition of Illinois this year). Particularly in light of the inevitable comparisons to Illinois, others are making connections to the “eerily similar” debates over decriminalization in New York in 1977 at the height of the state-level decriminalization wave that was then spreading throughout the country. During that year the New York State legislature passed, and then-Governor Hugh Carey signed, what was at the time the ninth state-level decriminalization measure in the country.

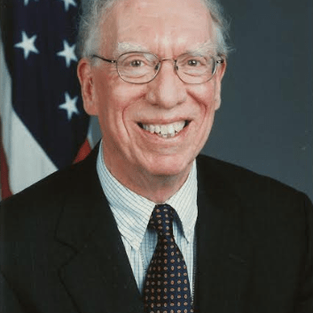

(Current New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, and then-Governor Hugh Carey)

And while New Yorkers, both then and now, see the easing of penalties, short of outright legalization, as an important step toward even more equitable legalization measures, it seems like state leaders are failing to learn from the lessons of the past (and present) about the reason why they are faced with a mass incarceration crisis in the first place. Drug historians have done plenty of work examining the “Just Say No” era of mass incarceration, but I’m not sure we’ve completely appreciated the contribution that decriminalization has had on creating and reproducing systemic inequalities in how we make and enforce policy on marijuana (and other drugs).

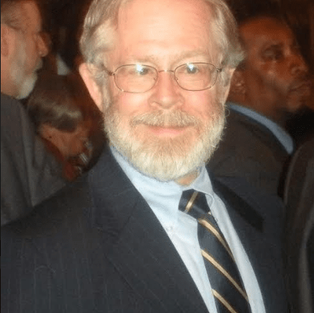

Prior to the decriminalization measure in 1977, and due in large part to the draconian Rockefeller laws, it was a misdemeanor in New York (with a penalty of up to a year in prison) to possess any quantity of marijuana and a felony to possess more than ¼ ounce (7 grams), with violators facing up to seven years in prison. According to NY Senator Richard Gottfried (D-Manhattan) at the time, “Nearly 30,000 New Yorkers are arrested every year…[costing] taxpayers millions, scarring countless [young] lives and breeding disrespect for the law.” [1] NY Senator Douglas Barclay (R-Pulaski)’s critique of marijuana laws was more pointed, “it’s time young people’s lives stopped being ruined by arbitrary and selective enforcement” of marijuana laws. [2]

(Doug Barclay and Richard Gottfried; both images from Wikipedia)

The two legislators teamed up to sponsor the 1977 decriminalization bill which sought to reduce the charge for possession of up to 35 grams of marijuana down to a violation subject to a $100 fine. After failing in its first go-around that session, a newly negotiated version re-emerged in the Assembly, and due (in part) to the emerging power of the Conservative party in state politics, the new bill passed with significant revisions, reducing the proposed “violation” threshold from 35 grams to 25 grams, while increasing the penalties for possession of ten pounds or more from 10 to 15 years in prison. Possession of between 25g to 8oz would be the new misdemeanor threshold, and possession of more carried felony charges.

I think we might be misinterpreting the significance of decriminalization. Granted, other factors (portended by the growing influence of the Conservative Party in New York politics in the 1977 legislative session) better explain the shift toward mass incarceration that began in the years following the decriminalization wave, but it stands to reason, based on the “concern for youth” trope that often informs prohibition narratives, that this was a concern for youth that informed liberalization narratives. And the result was to legally shield young, mostly white and middle class users from the penalties enacted during the “Just Say No” era of drug policy and enforcement, and the emergence of “stop and frisk” which can turn a small possession issue into a felony incarceration. Legislators also cracked down on major trafficking. While wringing their hands over “unjust” criminal records born of the “senseless crimes of youth” they enthusiastically slapped higher penalties for possession of more weight.

Upon signing the bill, Governor Carey signaled a willingness to pardon those currently incarcerated for possession of the new “violation”-levels of possession, and I was surprised that those pardons would have only impacted a relative handful of the 30,000 citizens arrested every year for marijuana possession. But what was even more surprising was the corresponding numbers of incarcerated citizens that would be impacted by the 2019 decriminalization bill. (The State Division of Criminal Justice Services estimates that 160,000 New Yorkers with low-level marijuana convictions would see their records automatically expunged, and the Drug Policy Alliance suggests the number could be much higher.)

Clearly the gap between major trafficker and small time “user” fails to take into account small-time users who ALSO sell to defray the costs of using their drug of choice. These folks are much more likely to be found in public in possession of between 25g and eight ounces (or now between 2 and 8 ounces) and who would face misdemeanor charges and a potential prison term.

And it seems that it is precisely those serving penalties for misdemeanor (and low level felony) charges who will see their charges expunged after this year, as a result of this next iteration of decriminalization, which prompted Governor Cuomo, in an August 28 tweet, to declare, “For too long, communities of color have been disproportionately impacted by laws governing marijuana. This law is long overdue.”

But is it? The major features of New York’s expanded decriminalization regime also dictate:

Possession of less than 2 ounces (57 grams) is a violation and not a crime. It is still arrestable, but no prison term or criminal record.

Penalty for possession of less than 1 ounce is lowered from $100 to $50. For 1-2 ounces it increases to a $200 penalty not subject to increase, regardless of criminal history.

“Most” convictions for possession of up to 2 ounces would be automatically expunged.

Marijuana use will be banned where smoking tobacco is banned.

None of these provisions actually address the factors that CAUSE racial disparities in arrests and incarcerations.

An article in Gothamist quoted Emma Goodman, a lawyer for the Legal Aid Society. She said that “[a violation] is still something that shows up on your record and stays with you for a very long time. And it can affect your ability to get jobs and housing and all of the things that criminal convictions can affect.” In an interview on WAMC, Melissa Moore of the Drug Policy Alliance cited a 2014 change in NYPD enforcement that did result in a significant decrease in overall arrests, but arrests were overwhelmingly people of color.

(Crystal Peoples-Stokes and Liz Kreuger. Will they get it right?)

Sponsors of the legalization bill (Sen Liz Kreuger D-Manhattan, and Assembly Majority Leader Crystal Peoples-Stokes D-Buffalo) are promising to push for legalization in the next legislative session. As I have argued elsewhere, the proposed legalization measure goes beyond limited enforcement threshold changes, which don’t really address racial disparities in policing. Instead, the proposal attempts to address the consequences of those racial disparities by investing in communities impacted by the War on Drugs. As the 1977 decriminalization drama demonstrated, changing possession thresholds does not address larger systemic disparities in the way that drug regulations are written and enforced.

NOTES:

[1] Donna Foster (NYS PTA Association), Letter to Editor, Wellsville Daily Reporter 18 Feb 1977.

[2] Drive to Ease Laws on Marijuana Aided,” NYT 17 March 1977