Interpreting Donald Trump’s “Oxy Electorate”: On the Interaction of Pain and Polit

- Points Editors

- Feb 2, 2017

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

On January 20 – inauguration day – the HBO news talk show Real Time with Bill Maher aired its fifteenth season premier. Unsurprisingly, Donald Trump was the topic of the hour. After Maher and his panel of pundits concluded their discussion, the host delivered an editorial monologue analyzing Trump’s electoral victory and offered a provocative comparison:

“Here on inauguration day, in the spirit of new beginnings, liberals have to stop calling Trump voters rubes and simpletons and instead reach out and feel their pain, the pain they insist we didn’t see. And there is ample evidence for that pain. Did you know that of the fourteen states with the highest painkiller prescriptions per person, they all went for Trump? Trump won eighty percent of the states that have the biggest heroin problem… So let’s stop calling Trump voters idiots and fools and call them what they are: fucking drug addicts!”

A screencapped image of a Vox article from late November, “Most Ohio and Pennsylvania counties that flipped from Obama to Trump are wracked by heroin,” levitated authoritatively over Maher’s shoulder during part of the segment and ostensibly inspired his conclusions. That article was actually reporting on new research from Kathleen Frydl, author of The Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973, and more recently “The Oxy Electorate,” which found that high rates of drug overdoses in a given county correlated with increased support for Trump.

Frydl’s report is striking. “In 9 of the Ohio counties that Trump successfully turned from Democrat to Republican, six log overdose rates well above the national norm. All of the Pennsylvania counties that chose Obama in 2012 and Trump in 2016 have exceptionally high overdose rates, averaging 25 people per 100,000; in none of these counties did vote totals fall.” And this phenomenon was not limited to red states: rural voters turned out for Trump in New Hampshire and New Mexico, wracked as they are by some of the highest overdose rates in the nation.

CDFBC booth at the Brown County fair. Image: Statnews

Where Maher superficially observes narcotic neophytes Jonesing for a quick fix to their political ailments, Frydl recognizes some legitimate grievances of Trump’s “oxy electorate”. The Obama administration’s modest efforts to combat drug addiction in the form of prescription “take back” events and block grants for addiction treatment made little difference in places like Brown County, Ohio, where the opioid overdose rate recently climbed to a staggering 40.2. Trump country earns similarly poor marks in rates of alcohol use, suicide, and economic mobility. The incoming president’s “Make America Great Again” slogan did not impress Brown County resident Tony Martin as much as a rhetorical question on the stump: “What have you got to lose?”

Per Frydl, these metrics “help to form a picture” of Trump’s appeal. But the public health crisis engendered by drug addiction is only suggestive and not alone explanatory. Neither does it, as Frydl writes, “undermine the convincing evidence that these voters were motivated by an ethno-nationalist appeal… Instead, it supplements it, providing a premise to help explain why a narrative of identity, place, and belonging would have such resonance among them.”

Perhaps there is one more suggestive-and-not-alone-explanatory piece to the puzzle: pain. Or, more accurately, a lack thereof.

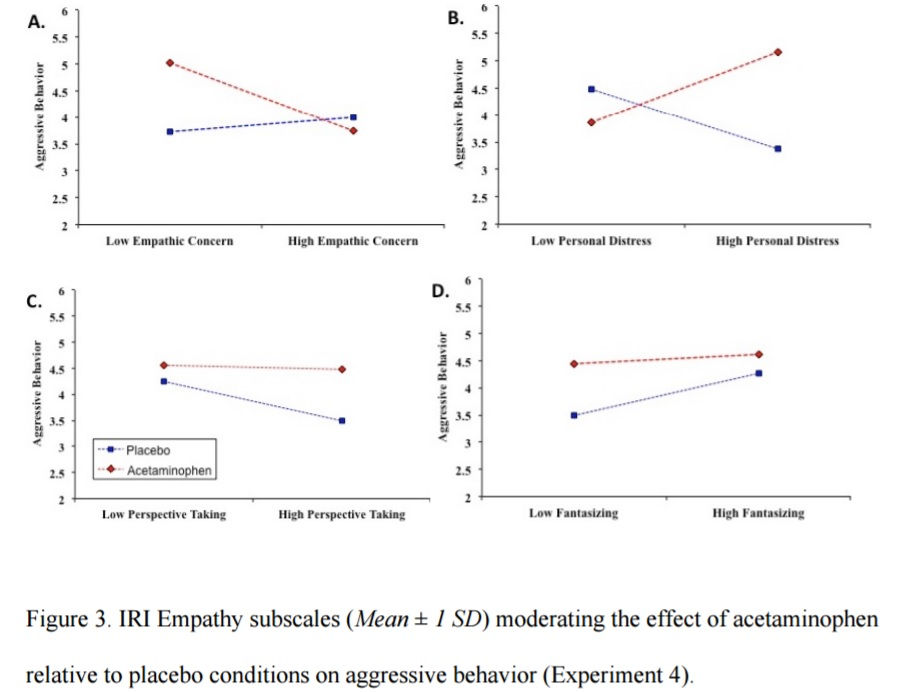

New research suggests that the use of acetaminophen, an anti-inflammatory analgesic, may negatively impact users’ capacity for empathy. In his 2015 dissertation, “The Social Side Effects of Acetaminophen,” Dominik Mischkowski measured the responses of three groups of participants given acetaminophen or placebo in three separate experiments. One exposed them to written vignettes of pain, another exposed them to someone else’s social ostracism, and the last exposed them to predetermined successes and failures in a computer game. In his analysis, the author concluded “that the experience of physical pain is fundamentally related to the experience of empathy for the pain of other people, indicating that pharmacologically reducing responsiveness to physical pain also reduces cognitive, affective, and behavioral responsiveness to the pain of others.”

One of Mischkowski’s tables (2015)

If Mischkowski’s findings hold true for other painkillers, they may help color in Frydl’s picture of suffering Trump supporters; namely, to explain their cognitive dissonance in the face of harms Trump proposed on the campaign trail and now executes as president.

A natural rejoinder might be that another potent, euphoric analgesic – marijuana – is used more frequently in blue states than red (save Alaska, the #1 outlier). Returning to Real Time, Maher has a theory: cultural familiarity. “We liberals invented stoned. This is common ground!” Perhaps he’s onto something. Points readers may be familiar with the pioneering work of scholars like Howard Becker and Norman Zinberg, who emphasized the social context of drug use to explain subjective drug experience. Set and setting matter. Marijuana’s modern status in pop culture evolved from an overt political statement of the Sixties-era pacifist left. Dating from the late Nineties and accelerating in the last decade, has the current, relatively new culture of opioid users simply not learned how to “manage” its high? “We get high and order a thousand-dollar Beatles lunchbox on eBay. You got high and ordered a president from Moscow.” No matter marijuana’s effects on our empathy, the public health tradeoff vis-à-vis opioids is a net positive; as of 2014, states with medicalized cannabis enjoyed 25% fewer opioid overdose deaths than those without.

I hardly need to state the importance of studying drugs on this blog, but their explanatory power may be even greater than we sometimes realize. Medication, self- or otherwise, signals a problem, perceived or actual. And it always has side effects.