In his last (for now, anyway) offering as a Points guest blogger, Eoin Cannon offers some thoughts on the aesthetics of redemption.

Noontime Prayer on Fulton Street, 1857

In my book-in-progress on the origins of modern recovery narrative, I look closely at the stories that came out of the post-Civil War “gospel rescue missions,” especially in New York City. These weren’t the first evangelical missions to the urban poor, of course. Specifically, they were outgrowths of similar activity during the Second Great Awakening, such as the New York City revival of 1857-58. Nor did they represent the first movement of reformed drunkards with tales to tell, emerging a couple of decades after the heyday of the Washingtonian Society. But, founded by the converts themselves in collaboration with their religious sponsors, the postbellum rescue missions combined revival, temperance, and moral reform in an unprecedented and very influential way. They moved evangelical religion in a therapeutic direction, and they acted as rebuttals to fatalistic social theory. Their growth drew social reformers to the slums to witness first-hand evidence that the far-gone drunkard and the vicious immigrant really could be changed. By the 1890s, the ex-drunkards and their patrons had produced a lively literature of conversion narratives.

The published narratives were occasionally accompanied by a fascinating before-and-after imagery. These images in particular made me realize how many historical formulations of addiction and/or recovery produce a visual rhetoric that encapsulates its particular understanding or innovation. Photographic images of the redeemed were paired with sketched recreations of what they looked like as drinkers. The effect is a transparent example of the biographical phenomenon whereby a subject’s life is constructed to fulfill the meaning of an ideologically controlling turning point–in this case, salvation. Here are a few examples.

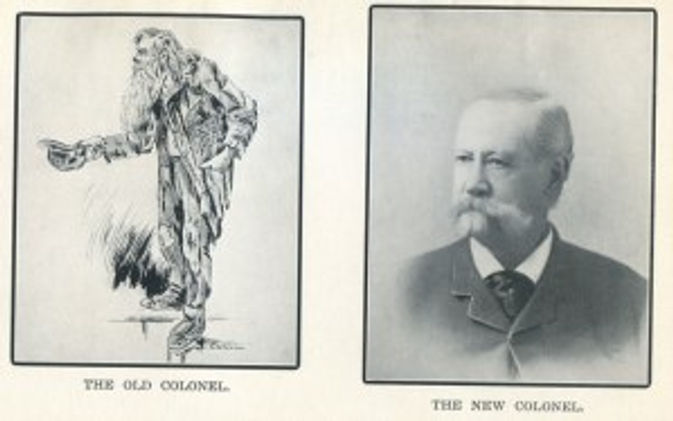

The Old Colonel and the New Colonel

The Old and New Colonels appear in Rev. Samuel Hopkins Hadley’s 1902 memoir Down in Water Street. At sixty years of age, after a lifetime of dissipation, “[h]is youth returned and he became, as the reader can see, a dignified Christian gentleman.” Said one missionary of the physiological effects of this improvement: “The Lord wipes out the lines.” (1)

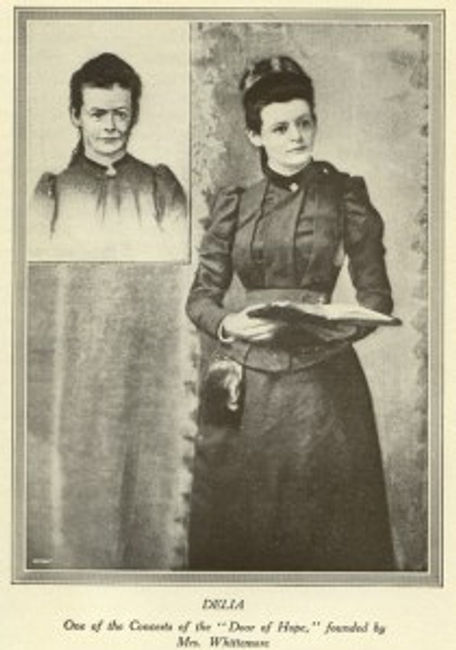

She is Entering the Kingdom of God Ahead of You (Matthew 21: 31)

Delia Loughlin, “The Bluebird of Mulberry Bend.” Note the bold, saucy eyes in the original, which her patron wrote was “taken” shortly after her rescue. The fact that the same verb applied to both drawing and photography suggests a reason why this apples-and-oranges contrast wasn’t obviously ridiculous in that era.

Jerry McAuley was the patron saint of the gospel temperance movement, an ex-drunkard and ex-Papist credited with its founding.

The Original Redeemed Man

McAuley’s face was described as having retained evidence of both sides of his life, making him a living embodiment of both sin and grace. “He was born to be bad,” one reformer recalled saying upon her first sight of McAuley. “How can he help it, with that type of head?” (2)

It’s easy to laugh at these earnest nineteenth-century typologies. Mark Twain sure did, when he wrote of Pap Finn’s brief reformation: “Look at it, gentlemen and ladies all; take a-hold of it; shake it. There’s a hand that was the hand of a hog; but it ain’t so no more; it’s the hand of a man….” But I’ll take these images of righteous reform over Faces of Meth any day. Despite the exclusionary nature of their religious vision, they provided escape valves from the airtight logics of the vicious poor and the ruined woman.

Notes (1) Helen Stuart Campbell, The Problem of the Poor. New York: Fords, Howard, & Hulbert, 1882. 64.

(2) Ibid, 14.