From Hippies to High Yield Insights: The Evolution of an Industry

- Emily Dufton

- Nov 29, 2018

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Mike Luce is not the first person to lament how increasingly banal marijuana becomes once the industry goes mainstream. Keith Stroup, who founded the nation’s oldest legalization lobbying firm, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), in 1970, told Rolling Stone in 1977 that the decade’s booming paraphernalia industry was developing just like anything else. “It’s a growth industry,” Stroup said, “that’s gonna be treated like tennis shoes must have been. I don’t say this out of any particular glee—I just think it’s a result of ‘the great free-enterprise system.’”

High Yield Insights, one of the nation’s first cannabis marketing research firms, this past May, feels similarly as recreational legalization expands. “From a great distance,” Luce said, the “classic marketing research” High Yield does for its clients—which includes everything from crafting tailored patient and consumer insight reports, to consulting medical and recreational businesses on strategy, growth, planning and innovation—is “very similar” to work he did previously, when he spent over 15 years researching audiences for a packaged food company. The only difference now, however, is that while these practices are commonplace for companies that sell soda, soap or tires, they simply haven’t existed in the cannabis industry before.

That’s changing, Luce said, as legalization spreads and more companies are entering the cannabis space. For groups that want to produce everything from high-end edibles to designer labels, High Yield offers “a way to introduce basic business information to a new and expanding field,” Luce said. In short, programs like Luce’s are helping cannabis become a legitimate business again.

Forty-one years have passed between Stroup and Luce’s quotes, but the tenor of their ideas remains the same: that marijuana is professionalizing and industrializing quickly, and we should be prepared for any effects.

The difference, however, is that, despite the confidence both men have in the future of their industries, Stroup knows what happened last time: the decriminalization movement of the 1970s launched a paraphernalia market that grew too fast, too quick. Pot has always been profitable, and when people rushed to cash in, the market expanded too rapidly. With no regulations or oversight in place, kids were marketed to, adolescent marijuana use spiked, and a counterrevolution began. In just a few years, the widespread decriminalization laws that were passed in the 1970s got overturned in the 80’s fervor of “Just Say No.” The strict anti-drug laws passed at the time are only beginning to be overturned today.

There are dangers inherent in cannabis’s rapid industrialization, Stroup knows. People can get blinded by profit motives, and the industry falls apart. Now, as legalization initiatives spread nationwide, he doesn’t want to see the same mistakes repeated again.

*

The history of the legal market for marijuana in America is a story that repeats itself. As recreational legalization initiatives are passed nationwide, today’s era of increased interest in pot marks the second time in the past half-century that Americans have had to readjust to cannabis and its associated products being marketed as regular consumer goods.

Forty years ago, when a dozen states decriminalized marijuana in the mid-1970s, the paraphernalia industry boomed in response. By 1977, the market was bringing in $250 million a year from the sale of pipes, bongs, rolling papers, toys and more—the equivalent of about a billion dollars today.

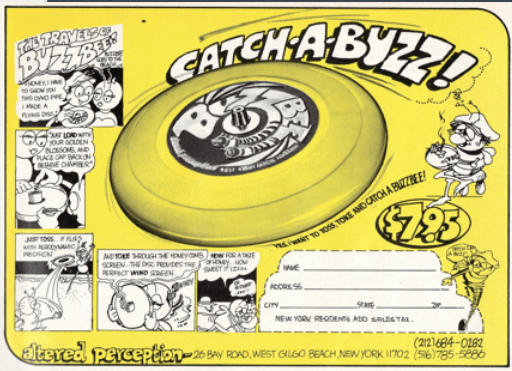

The BuzzBee, one of the paraphernalia market’s bigger mistakes in the 1970s

But as the industry blossomed, it lost sight of itself. Bongs were sold everywhere from high-end headshops to 7-11s, staffed by cashiers who never bothered to checked IDs. Kids had easy access to the drug culture: ads in magazines like High Times and Stone Age featured clowns and Frisbees that explicitly appealed to them, while a New York Times report from 1978 showed that a bunch of 11-year-olds could buy anything at a head shop if they had some cash. In response, rates of adolescent cannabis use spiked. By 1979, 11% of high school seniors reported using the drug every day, and children as young as 13 said that the drug was “easy to get.” A national backlash of concerned parents formed in response, and they partnered with increasingly conservative state and federal lawmakers in the 1980s to crack down on pot and spread the gospel of “Just Say No.” The virulently anti-drug movement of the 1980s was a direct response to how widely available, and widely accepted, the marijuana market was in the 1970s.

Effectively ousted from mainstream commercial culture, by the 1980s the marijuana market went back underground, and it didn’t reemerge until the movement for medical marijuana began in 1996. But the small medical outlets of the 1990s and early 2000s were nothing compared to today, when recreationally-legalized marijuana sales are bringing in billions of dollars annually, there are thousands of licensed cannabis businesses across the country, and more than 100,000 people are actively employed in the industry.

Today, as legalization laws spread nationwide, cannabis and its associated products are leaving the black market behind, and the industry has evolved in response. Legalization in the 2010s mirrors our growing national interest in good design. Sleek vapes, artistic edibles and premium flowers are sold in even sleeker stores, while niche artisans make cannabis cold-brew and CBD-infused sunscreen. And the robust sales and the growing number of products available means that, as marijuana goes mainstream, it’s also going increasingly middle-class.

But just like in the 1970s, there’s a backlash forming now, too. Voters in Colorado were upset when rates of kids’ emergency room visits for marijuana spiked after the state legalized in 2012, and many continue to wonder about legalization’s effects on public health and safety. Of particular concern are infused edibles, which, in many places, look like regular candy. Kevin Sabet, of Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM), is one of the most vocal critics of legalization, and he has campaigned in states that are considering legalization like Michigan, warning that “rich white guys” are going to “sell pot gummy bears.” Not everyone agrees that this is a bad thing, of course. California, which has tried to counteract products that appeal to kids by enforcing strict laws on edibles packaging and sale, has received complaints that their cartoon-free, clearly-labeled packages are “boring.”

There are also fears of growing corporate interest in pot. As major alcohol companies like Heineken and Constellation Brands enter the marijuana sphere, fears are continually being stoked about the threat of Big Marijuana. Critics like Sabet warn that a soulless corporate monopoly is inevitable, and that it will prey on children with a new generation of cannabis-oriented Joe Camels.

But that’s not the only backlash around. The legalization and professionalization of cannabis can, surprisingly, be as difficult for those in the business as those outside it. Marijuana going mainstream means that the industry loses some of its outlaw status, a loss that farmers in places like the Emerald Triangle feel deeply. And it’s obviously problematic when “ganjapreneurs” are celebrated for their business savvy today, when so many millions of people have spent the past three decades incarcerated for using and selling the same drug.

Despite breathless pronouncements that the American cannabis industry will soon be bigger than corn, there is a growing chorus of voices asking the industry to slow down and ask itself some meaningful questions before it rushes ahead. When I spoke to Stroup again in January of this year, he said that he thought the most successful future for cannabis would be if it were modeled on craft beer and wine, with small producers and artisanal style. Ryan Stoa’s new book Craft Weed: Family Farming and the Future of the Marijuana Industry argues the same thing. Stoa believes that, if the industry stays small, it could be mutually beneficial, serving as a boon to America’s struggling small farms, while allowing the industry to remain adults-only and above-board. Luce is similarly in agreement. “The industry should absolutely self-police,” he said. “If it develops a track record of finding, identifying, and solving problems, it can cultivate better relationships and make more consumer-friendly products.”

More people are joining Stroup, Stoa and Luce, and are wondering if we can stop the problem of cannabis’s hyper-industrialization before it begins. They’re fearful that a growing number of people will rush to exploit the profit potential in pot, and that an industry that is only beginning to emerge from the black market will immediately be co-opted by those who only seek financial gain.

If history is any guide, this could be a very good thing. If these conversations continue, the cannabis industry might do something new—and something it certainly didn’t do in the 1970s. Forty years after our first failed experiment with decriminalization, the cannabis industry could effectively regulate itself. In doing so, it could stay small, stay solvent, stay legal, and, most importantly, learn useful lessons from the mistakes of our past.