From ‘Drill, Baby, Drill’ to ‘Grow, Hemp, Grow’: Reflections on Industrial Hemp and Foreign Oil

- Adam Rathge

- Jul 3, 2014

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2023

Since the early 1970s, most Americans have been keenly aware of the effect foreign oil production and supply can have on the economy and national security interests of the United States. From the 1973 OAPEC embargo to the 1979 Iranian Revolution to more recent debates on the Keystone pipeline or Deepwater Horizon spill, the importance of “energy independence” has been a recurring theme for decades. But it may come as a surprise that similar rhetoric once surrounded a reliance on foreign hemp.

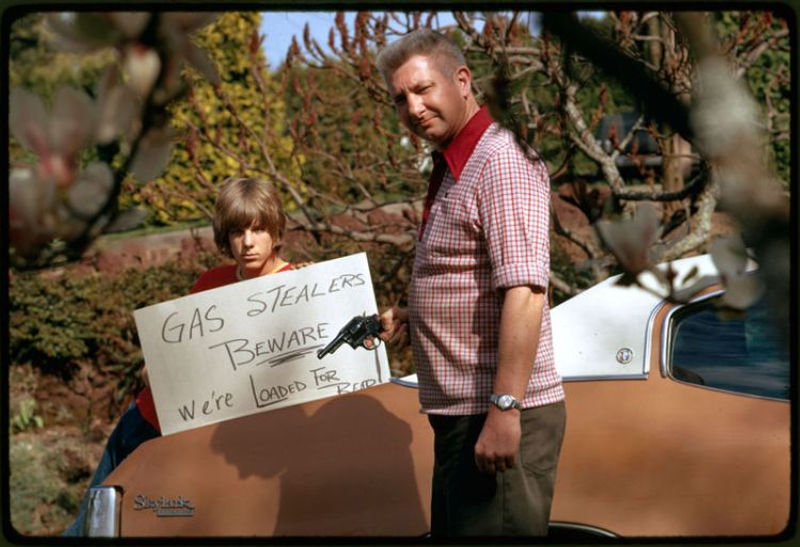

Father and son hold up a sign saying “Gas Stealers Beware, We’re Loaded…” during the 1973 Oil Crisis (David Falconer, EPA, US National Archives)

To make this (admittedly imperfect) comparison, we begin in the 12th century– when, as historian Bradley J. Borougerdi shows, the burgeoning dominance of the Hanseatic League allowed superior Russian hemp to flow into Europe for the first time. During the Age of Exploration, the need for steady hemp supplies among Europe’s emerging naval powers grew to ever increasing heights. Like oil in the twentieth century, hemp was, according to Borougerdi, “a practical and strategic necessity for becoming a dominant power on a large scale.”

The problem was that much of that hemp supply continued to come from Russia. With such demand and importance, European powers sought to establish hemp independence by growing sources at home and in their newly established colonial empires. The French, the Portuguese, and the Dutch established ropewalks and produced hemp canvas for their ships. The Spanish made the first attempts at hemp cultivation in the New World when the crown encouraged the practice in 1545. The English effort to secure a steady supply of British-grown hemp focused on the Americas as well, where the settlers of Jamestown were instructed to grow the plant.

Hemp Crop – Not in Jamestown. Attribution: Adrian Cable http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1470339

Borougerdi’s recently defended dissertation also suggests the English were especially concerned with relying too heavily on hemp imports from foreign countries, particularly Russia. Such a valuable and necessary commodity could be (and often was) interrupted by imperial conflicts and shifting alliances. A sudden decline in hemp supply could therefore drain the country of its naval stores, leaving them in a vulnerable position in the race for empire. The fear fostered by this overreliance on foreign hemp continually spurred legislative action. Virginia enacted mandatory hemp production in 1633 and again in 1673. Further efforts required seed for hemp cultivation be distributed so “that the necessities thereof be supplyed from their owne industry within themselves, and that the lesse they have occasion for from abroad, the lesse wilbe their dependance on forreigne supplies whereof the calamity of warr and other accidents may prevent them.” Colonial governments in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and areas of New England also heeded the call to encourage cultivation and reduce reliance on foreign hemp.

Following the American Revolution, both the English and the newly independent American states continued to rely heavily on Russian imports while working to encourage and bolster hemp production of their own. The British turned to colonial India while American growers sought to meet their needs with home grown supplies. They found that hemp was not difficult to grow, but it was rather onerous to transform the crop into the valuable fiber needed for naval stores or sale on the international market. Both countries failed to achieve hemp independence. The Americans continued to rely on international trade, while the British encountered an Indian population far more familiar with the intoxicating uses of the cannabis plant than the industrial uses the English so desired. The inability to produce enough hemp domestically or colonially played an important role in transforming perceptions of the plant in the Atlantic world.

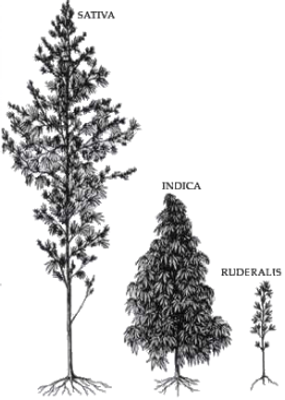

The exact species classifications of cannabis are still the subject of some debate. C. sativa is best suited for industrial hemp, but it also has medicinal and intoxicating varieties.

Part of this transformation stemmed from the complicated nature of the plant. Hemp is derived from Cannabis – a genus of flowering plants that is generally considered to have multiple species: Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, the two most well recognized, and Cannabis ruderalis, a source of continuing debate. Hemp varieties contain only trace amounts of the psychoactive cannabinoids in the plant necessary to “get high,” while intoxicating varieties generally yield inferior fiber. This difference reflects the incredible genetic diversity of cannabis plants, which can be further heightened by its susceptibility to changes in environmental growing conditions and human manipulation. Nevertheless, most cannabis plants tend to look somewhat similar, a fact that led to some degree of confusion and debate among Europeans following the classification and categorization of cannabis by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 and Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in 1785. Add the fact that cannabis has been utilized in myriad ways throughout recorded history – Intoxicant, Fiber, Medicine, and Oil – and one begins to grasp how easily the plant has meant different things to different people.

The sharp division drawn by Europeans in the nineteenth century between its “productive, industrial” uses at home and its “degenerative, intoxicating uses” in India proved especially important. The term “Indian hemp” quickly came to signify these “oriental uses” and spread to the United States alongside the medicinal research on the plant. The strategic value of hemp fiber led the British to deplore the intoxicating uses they observed, slowly eroding the perception of the plant as a necessary strategic commodity. The two uses were nonetheless linked to one plant, and as the importance of hemp fiber declined the intoxicating perceptions of cannabis prevailed. In large measure, this transformation in perception helped shape the nature of cannabis prohibition in the early twentieth century (something I’ll cover in my dissertation) and has continued to color recent debates on the re-introduction of industrial hemp in the United States. Now that perception appears to be changing once again.

Alongside the push for the legalization of medical and recreational uses of cannabis in recent decades, a renewed belief in the productive nature of industrial hemp has emerged in the United States, complete with pro-hemp twitter handles. The movement gained significant traction earlier this year thanks to an amendment in the recently passed farm bill allowing states to remove legal restrictions and begin growing hemp for research and testing. Some sixteen states have now taken such action. Among these, Kentucky went so far as to sue the federal government after the DEA seized hemp seeds destined for the Bluegrass State. Seeds headed from Canada to Colorado were also held up last month at the North Dakota border. Colorado, the first state to legalize recreational marijuana, is also ahead on industrial hemp; it’s already passed a state law allowing commercial cultivation. Both Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and Rand Paul (R-KY) have supported hemp legalization and slammed the DEA’s recent actions. Representative Thomas Massie (R-KY) recently added and successfully passed an amendment to a bill that controls the DEA’s budget and specifically protects imported hemp seeds from seizure. Kentucky has deep historical roots as one of the nation’s hemp producers, and its legislators are aggressively seeking the return of what they see as a viable cash crop. That sentiment was echoed by Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, who called industrial hemp an “extraordinary income opportunity.” Indeed, in Canada, where hemp cultivation has been legal since 1988, the industry produces nearly $1 billion a year.

Cutting Hemp in Kentucky – The state’s first hemp crop was grown in 1775. (Postcard Collection, Kentucky’s Digital Library)

Here, the rhetoric of oil and hemp converge in new yet familiar ways. Renewed calls for hemp independence often point out that the United States already imports hundreds of millions of dollars of foreign hemp each year and that hemp industries elsewhere around the world have a leg-up on domestic American production. There are also those who believe hemp could be the ticket to beating climate change, effectively replacing a range of petroleum products and reducing carbon emissions. Hemp can also be used for numerous products — from clothing to paper to insulation– and can often grow in soil depleted by crops like tobacco or cotton. As part of the newly-legal research provisions, the University of Hawaii’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (CTAHR) began a two-year study to explore whether hemp can remove toxins from contaminated soil. CTHAR is also investigating as its potential use as a biofuel crop, thereby reducing reliance on foreign oil and aiding in the quest for energy independence.

From foreign hemp to foreign oil and back again. While the green revolution touted by today’s hemp enthusiasts may differ from the oil and hemp independence rhetoric of decades and centuries gone by, the strategic and economic concerns at the center of the debate remain much the same.