Deadly Intoxication, or: A Series of Odd Coincidences

- Alexine Fleck

- Jul 1, 2014

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

“This pussy has teeth; no one should fuck me ever” — Margaret

I begin this post with exciting news: Slava Tsukerman and Anne Carlisle are collaborating on either a sequel to or a documentary about the making of Liquid Sky, the 1982 science fiction movie about Margaret, the new wave Edie Sedgewick-inspired club-hopping model who, assisted by her alien lover, kills with her cunt.

A summary is all but impossible, but here goes:

Liquid Sky is set in the underground post-punk, new wave, heroin infused world of New York’s club culture. Margaret’s life is the inversion of all that is normal: she sleeps all day and spends her nights with an assortment of models, drug addicts, dealers, creeps, and hangers-on. Everyone looks profoundly bored and alienated, all vacant-eyed, one-dimensional, and oozing Baudelairean spleen. (Or they are really bad actors; it’s hard to tell). An alien craft lands near Margaret’s penthouse apartment. The alien inside nourishes itself on opiate-intoxicated brains before discovering that the orgasmic brain produces an even more delicious chemical. Suddenly, opiates and orgasms become fatal.

A clearly confused New York Times reviewer describes the alien’s reaction to the delicious brain chemical as an “explosion of what looks like an electronic meatball.”

Margaret is the alien’s vector, and anyone who has an orgasm with her is consumed by the hungry alien. While the first victim, Margaret’s former lover, Owen, dies from a glass shard in his head, leaving behind an inconvenient body, the rest are simply vaporized. The body count includes: Paul, a middle class junkie who rapes Margaret after being rejected by his wife; Jimmy, Margaret’s loathsome rival; and Adrian, Margaret’s abusive girlfriend. Margaret understands both the deaths of these attackers and their subsequent disappearances as a loving gesture from the alien– who, she realizes, is her true love. Once she discovers her power to kill, Margaret seeks revenge on Vincent, the creep who raped her, tracking him down and seducing him with the knowledge that he will pay for his violence with his life. Her last act of revenge complete, Margaret puts on a wedding dress and injects herself with heroin in order to be sucked, happily ever after, into the spaceship with her alien true love.

Confused? The clip below is the best summary/analysis I found online. It also allows those who can’t or won’t watch the movie (which deserves the Mother of All Trigger Warnings) to get a sense of the “aesthetic” of the film without being exposed to the more awful parts.

The title of the movie was based on a relatively new term for heroin, but the phrase “liquid sky” can be traced as far back as Spenser’s Faerie Queene, which compares the movement of a boat to a swallow slicing through the “liquid sky.” A quick perusal of academic articles suggests that it is a surprisingly popular poetic phrase, an evocative description of a of natural sky appearing solid enough that spirits can walk upon it, or an eagle can “cleave” it in search of a tasty dove.

Heroine with syringe

Within the imagery of the movie, “liquid sky” likewise describes the incredibly beautiful shots of the New York skyline cleaved, this time, by an alien invader. With its obsessive return to the Empire State Building, which looks remarkably like a hypodermic syringe drawing up “liquid sky,” the phrase implies that the sky above is a loving opiate into which one can escape, as Margaret does at the end of the movie.

One reviewer was particularly taken with the idea of the film as a love story, moving “from rape to marriage,” through an Hegelian thesis (abuse) to antithesis (revenge) to synthesis (‘marriage’ with alien). In this way, the reviewer suggests, “liquid sky” can be read as a “beautiful metaphor for love’s ecstasy.” Ecstasy, I would add, derives from ekstasis (standing outside oneself), an etymology that becomes particularly provocative in light of the novelized version of the movie I discuss later in this post.

More specifically, however, as one character explains, “liquid sky” refers to the ability of heroin to transform the user into a more pure and artistic self, one who can see through the veneer of a nonsensical “normal” life much as one can look both at and through the sky. The phrase itself, a sort of self-contradicting fusion of opposing elements, implies a blurring of boundaries between day and night, depth and height, “normal” and countercultural, perception and reality, and, of course, human and alien. Additionally, heroin in particular contains a paradox of seemingly opposed elements. A user appears down, unconscious, and unproductive from the outside, but from the inside, a heroin “high” feels transcendent. Before opiates were widely feared and regulated, artists and poets frequently relied on intoxication to access their creative minds and produce literature that has become firmly ensconced in the canon. Of course, many of them paid dearly for their use, but nonetheless: intoxication had its uses then and now.

Baudelaire, who was fond of opiates. All the translations of “Le Serpent Qui Danse” sacrificed an exact translation for rhyme scheme. If you want to see a more literal translation, click on “un ciel liquide”

It is a delightful coincidence, then, to discover that Liquid Sky is not the first text to connect the phrase to the ecstatic consumption of an intoxicating substance as opposed to a figurative description of the actual sky. In “Le Serpent qui Danse,” Charles Baudelaire compares “un ciel liquide” to the intoxicating experience of kissing his beloved. The poem moves through metaphoric descriptions of the woman’s skin, hair, eyes, head, and body. In the final two stanzas, the speaker describes tasting the water of melted glaciers on his beloved’s lips. The experience is like drinking Bohemian wine, filling his heart with the dazzling light of scattered stars. Taken in the context of this reading, “liquid sky,” which Baudelaire describes as bitter and conquering, might very well refer to laudanum on the lips of his lover, or perhaps to the enthralling experience of kissing her wondrous mouth. The power of this opiate embrace scatters the expansive sky of intoxication into the speaker’s heart, overwhelming him to the point of seeing stars. In this reading, the woman he describes is intoxicating the way opiates are intoxicating, and the speaker’s consumption of them both is what produces his bliss.

not waving, but drowning?

I wonder, however, if the poem is also about the danger of such ecstatic consumption. In this interpretation, the speaker is lured to set sail “for a distant sky” in part by the beloved’s eyes, which are “sweet and bitter” blends of iron and gold, perhaps a reference to the Gold Rush and, in particular, “fool’s gold,” an iron pyrite that often looked like gold. As with many hapless minors, then, the speaker is undergoing a dangerous journey for, possibly, nothing of real value.

With its many nautical references, “Le Serpent qui Danse” is also a poem about drowning. The beloved’s skin is like the sail of a boat, her hair becomes the sea, her head the billowing of the sails dancing around the central mast that anchors them. Then, the woman becomes the boat itself, rolling side to side so that the ship’s yards plunge into the water. A yard is the cross bar on the mast, which anchors the sail. If it plunges into the ocean, then the boat has capsized. In this interpretation, the water that reaches the edges of one’s teeth is the ocean. All is inverted; sky becomes water as the boat begins to sink. The bitter, conquering Bohemian wine becomes a literal liquid sky as the speaker, gasping for air, inhales water instead. As he loses consciousness, the speaker sees stars.

The “yard” is the bar perpendicular to the mast. If it plunges into the water, you’re kind of in trouble. (This a French boat in 1842)

This second interpretation, one that demands the reader simultaneously recognize intoxication and death, suggests another way to interpret Margaret in the movie. Rather than being only the one who is desired and consumed, Margaret becomes the woman who guarantees the destruction of all those around her. She is an unstable vessel who intoxicates, and then destroys, anyone who dares seek an adventure on her body. Their moment of pleasure is also their moment of death – indeed, it guarantees it.

It is ironic to note that this conflation of intoxication with death both reflects the danger inherent to drug use and anticipates the arrival of a deadly new disease. With its suggestion that Margaret’s body acts as a vector for the destruction of young bodies through acts of sex and heroin use, the film could be read as an early parable about HIV/AIDS. This connection is only coincidental, however, as GRID was still confined to the gay community and the term AIDS was first used by the CDC a month after Liquid Sky was released. So, an odd coincidence, but nothing more.

It is also ironic to note that the scientist’s theory about heroin and orgasm producing molecules in the brain likewise anticipated the later attempts to locate addiction in the brain as opposed to figuring it within an experiential framework.

And what are the odds that an actress from Liquid Sky later became the stewardess who made announcements and directed the passengers on Flight 93, which crashed into a field on September 11th, 2001.

Or this: “Me and My Rhythm Box” lives on in experimental music.

And this: the idea of rape as something other than the actions of a pathological stranger was still relatively new in public imagination. “Rape culture” as a term and concept was still primarily circulating in feminist communities, as were terms like “domestic violence,” “marital rape,” “date rape,” and “date rape drugs.” More odd coincidences, I’m afraid, presented primarily for your reading (and possibly, viewing) entertainment.

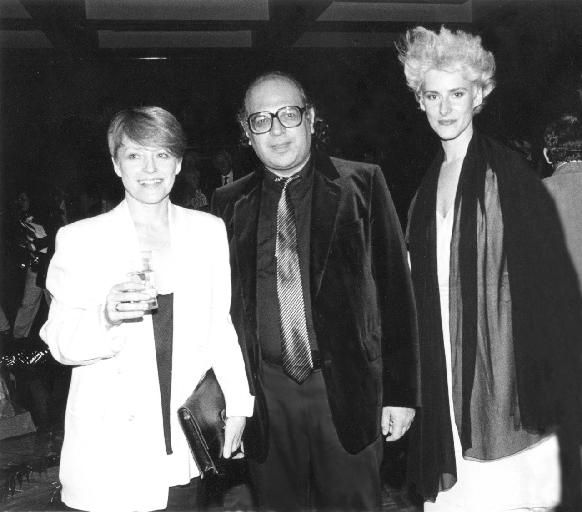

Producer Nina V. Kerova; co-author Slava Tsukerman; and co-author/actress Anne Carlisle

According to Carlisle’s interview for Playboy, Slava Tsukerman originally suggested to Anne Carlisle that they “write a script about a New Wave model who gets visited by an alien from outer space.” I guess things just went from there. The adventures of Margaret were based a little on Carlisle’s own experience. Like Margaret, Carlisle arrived in New York still very much a traditional lass, but she eventually realized that by “putting myself in the position of the victim, wanting to please,” Carlisle explained, she was “being a victim.” She decided to cut off her hair and embrace androgyny as a way to escape the danger of these sex roles. The fact that Margaret is able to destroy all of the people who sexually abuse her with the help of her alien lover, then, can be viewed very much as a fantasy tale of revenge. Margaret’s concluding monologue about how men and women both abuse her (and the only thing to do now is to dance) probably reflects Carlisle’s growing awareness that there is no escape from culture except, perhaps, on an alien spacecraft.

Her 1984 Playboy interview and photo shoot suggests that Carlisle has reinterpreted Margaret again. She says that she “went to see the movie again recently, in fact, and got very angry at her. Margaret is a victim.” This interview is not Carlisle’s last word on Margaret, however. Three years later, in 1987, she published a novelized version of Liquid Sky in which she completely recast the story.

Rather than a victim who gains her revenge and manages to escape the meaningless and cruel world she inhabits, Margaret is represented as a deeply traumatized woman prone to periods of dissociation. After each assault, Margaret slips away (ekstasis!) – either going unconscious or slipping into an alternate person who views Margaret from outside. (For those of you familiar with the movie: the German scientist, Sylvia, and Katharine are all figments of Margaret’s imagination). When Margaret regains consciousness and finds herself alone, she concludes that an alien is consuming them, literalizing (at least in her addled mind) the petit mort. The only person who actually dies is Owen, the man who assaults her immediately after her rape.

Convinced that everyone has died, Margaret injects heroin to be united with her alien lover. When police arrive after neighbors report the smell, they find Owen in his box and Margaret, dangling from the edge of the roof by her wedding dress.

And I thought the movie was depressing!

There is no revenge. Vincent gets to have sex with Margaret again. Paul gets to rape Margaret with no consequence. Margaret’s coerced sexual performance with Jimmy becomes an edgy fashion spread. Adrian runs off to Berlin. And the patrolman who finds Margaret’s body “took a reflective moment and really looked at the girl. He thought, It’s sad that she died. She seems like someone I could like. She must have been sexy.” Then, the police close the case as a murder/suicide.

sound familiar? “Sir Lancelot mused a little space; He said, ‘she has a lovely face.'” Women who wear wedding dresses in search of their perfect love (but dying instead) are nothing new.

Gah!

In addition to this radical re-interpretation, the novel also offers an insight into what all these cool, alienated people felt, which was mostly panic. All the characters are drowning in emotional excess as they try to figure out how to survive in the cruel, parasitic world they have created. The novelized version of Liquid Sky asks us to understand that there are stories we cannot even imagine in the minds of those we might write off as junkies and whores. It argues that we should not quickly dismiss the grand, yet ultimately powerless, gestures of a traumatized woman by noting that she must have been sexy.

So, what do I make of all this? A movie project that might be a documentary or a sequel; a novel that completely re-interprets the movie; a series of odd and mostly coincidental allusions; an historical interpretation only possible through time travel?

I think that the movie might be seen most provocatively as a story about intoxication disengaged from addiction. This was, after all, the moment just before HIV/AIDS, before sex became fatal in people’s imagination (and not in that “little death” sort of way). This film marks the last moments before a radical shift in the way we think about the dangers inherent to sex and drug use. It is worth noting, then, that the cause of death is not use, but intoxication itself. At the cusp of the excesses of the 1980s, this movie argues that pleasure itself is what is fatal.

One consequence of HIV/AIDS and the rise of recovery culture is that the dangerous pleasures of intoxication are lost. Yet, it is an inconvenient truth that drug use, like sex, is also about pleasure – transcendence even. The quest for dangerous pleasures can put a person in grave danger, particularly at the hands of abusive parasites, but it can also reflect the very human desire to find what is beyond the liquid sky.