Conference Summary: “I’ve Been to Dwight,” July 14-18, 2016, Dwight, IL

- David Korostyshevsky

- Aug 23, 2016

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Editor’s Note: This conference summary is brought to you by David Korostyshevsky, a doctoral student in the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine at the University of Minnesota. He traveled to Dwight, Illinois, in mid-July to attend the ADHS off-year “I’ve Been to Dwight” conference, and has provided this account of his time there. Thanks David!

On July 14-18, 2016, a group of international alcohol and drug historians descended upon the village of Dwight, Illinois, for an ADHS off-year conference. Conference organizers selected Dwight because 2016 marks the 50th anniversary of the closing of the Keeley Institute.

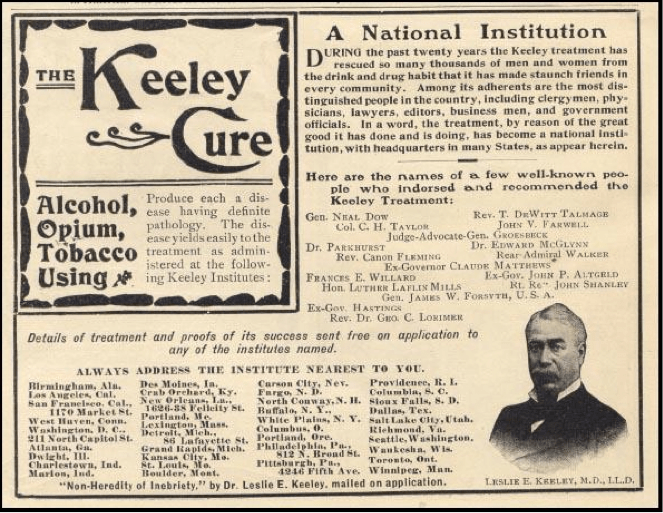

Founded by Leslie E. Keeley in 1879 (and operating until 1966), the Keeley Institute offered treatment options to patients with addiction, usually alcoholism, including Keeley’s Gold Cure. “I’ve Been to Dwight,” the conference title, references “a catchphrase” former Keeley Institute patients “used to explain their sobriety.”

To make it easier to read, this summary is organized thematically. You can see the full conference program here.

I live-tweeted the conference as @rndmhistorian under the hashtag #IBTD16. Also, Janet Olson, volunteer archivist at the Frances Willard Historical Association wrote a blog post about the conference.

Food and Addiction

The conference opened on Thursday evening with a keynote address by Sarah W. Tracy, who addressed the transformation of food addiction from a metaphor to a diagnostic category.

This conceptual shift is informed by the emergence of neuroscience. Specifically, fMRI imaging studies suggest that some sugar and fat-rich foods activate similar centers in the brain that are engaged by addictive drugs such as cocaine. Tracy also showed that the corporate food industry has adopted many of the tactics of the tobacco industry, engineering processed food so that it is as palatable as possible to ensure consumer loyalty.

But while addiction to industrial technofood may very well be a “real” thing, Tracy urges us not to allow it to become a catchall category that distracts from other complex social issues such as public school food, subsidies for corn and soy, and urban food deserts.

Borders and Boundaries

Conference papers kicked off with a familiar theme: the significance and ambiguity of borders (be they conceptual, geographic, or temporal). Describing Canada’s nineteenth-century temperance laws, Dan Malleck demonstrated the fuzzy, difficult-to-legally-define boundary between leisure drinking and the medicinal use of alcohol. Andrae Marak spoke about literal borders, concluding that smugglers and the state exist in a symbiotic relationship that continues to ensure unceasing cross-border drug flows.

Drug use practices also blur lines separating different substances, aptly illustrated by Alexandre Marchant’s discussion of multiple drug use in France during the 1960-70s. French lawmakers, law enforcement, and medical professionals were challenged by polyaddiction as they considered the needs both of individual addicts and society.

Papers by David Korostyshevsky and Elizabeth Kelly Gray examined the relationship between alcohol and opium in nineteenth-century American temperance discourses. According to Korostyshevsky, many temperance writers regarded alcohol and opium as similarly threatening intoxicants. Meanwhile, Gray revealed that as temperance agitation made drinking disreputable, some drinkers switched to secret laudanum use, the growing awareness of which posed “a hard lesson for temperance men.”

Panel featuring David Korostyshevsky, Elizabeth Kelly Gray and Josh Steedman

Intoxication, Addiction, and Gender

The importance of gender was also a prominent theme of conference scholarship. Michele Rotunda showed that the emphasis of domestic violence in Washingtonian narratives reflected the reality of nineteenth-century drinking in America.

Papers about the American South also resonated strongly with the running theme of gender. James Hill Welborn III argued that drinking was one of the contexts in which Southern honor and manhood was defined, while Sarah Lirley McCune found that class and gender determined whether a woman’s alcohol-related death was ruled due to dipsomania, a more sympathetic medical category than intemperance.

Other papers in which gender figured prominently were Andrei Guadarrama’s study of women’s drinking in revolutionary Mexico, Thora Hand’s look at a late-Victorian moral panic about women drinking tonic wines, and Colin Eager’s work on the early-1980s emergence of Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

“Not for the Squeamish”: Gender, Addiction, and Big Data

A Saturday-morning roundtable panel, advertised as “Not for the Squeamish,” urges historians and scientists to collaborate more closely. Moderated by Nancy D. Campbell, panelists explored multi-, inter-, and trans-disciplinary approaches to studying addiction.

The participants, all from the University of Michigan, included historian Michelle McClellan, neuroscientist Jill Becker, professor of social work Beth Glover Reed, and M. Leonora Bowden, a nurse and medical practitioner. Each member of the group brought a particular area of expertise to bear on a larger project to glean knowledge about addiction, gender, and families from big data sets generated by the Michigan Longitudinal Study.

Important scientific concepts with which the panel engaged include neuroplasticity, brain imaging, and epigenetics. It was especially fascinating to hear how each member of the group, each coming from vastly different professional worlds, gradually learned to understand one another’s assumptions, methods, and approaches to a common problem.

The Role of Science

Another prominent conference theme revolved around the role of science in shaping medical and public perceptions of alcohol, drugs, and addiction. Annemarie McAllister explained that in the late-Victorian period, public demonstrations of alcohol chemistry popularized scientific temperance knowledge. In turn, social reformers produced reading materials aimed at children, women, and families that sensationalized scientific knowledge about alcohol and drugs in order to teach moral lessons.

Within the realm of treatment, medical science encountered difficulty in determining the efficacy of proposed cures for addiction. Caroline Clark showed how the scientific trials of treatment that followed Australia’s 1899 Inquiry into the Treatment of Inebriates reveal the tension between medical and social models of inebriety at the end of the nineteenth century. Similarly, Sidsel Eriksen studied how physicians in Denmark evaluated treatments such as Keeley’s Gold Cure as they spread beyond the United States.

Drugs, Race, and Mass Incarceration

Many papers also explored the relationship between the War on Drugs, race, and the rise of mass incarceration. Michael J. Durfee argued that the 1980s crack era in New York represented a watershed moment in the decline of community policing and the militarization of police forces. Police routinely ignored the priorities of community leaders in favor of heavy-handed crime control tactics.

Focusing directly on institutions of incarceration, Holly Karibo posited that the Fort Worth Narcotics Hospital helped lay the groundwork for the rise of the American carceral state. Built in a context when prison reformers sought to make institutions a site for rehabilitation, the prison-hospital literally constructed a prisoner-patient model.

Looking at the politics of methadone in 1970s New York, Kyle A. Bridge showed that issues of policing and incarceration became powerful metaphors in treatment discourses. While its inventors saw it as a magic-bullet addiction medication, black community leaders feared that the maintenance model of treatment and methadone’s side-effects were a tool of racial social control that kept New York’s poor blacks in “liquid handcuffs.”

Inter/Transnational Perspectives

It is remarkable that “I’ve Been to Dwight” attracted strong international participation. Attendees came from the United States, of course, but also the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, France, Denmark, and Mexico. And despite a heavy focus on the United States and the United Kingdom, presenters also included a variety of locations in their analyses, including transnational contexts and non-Western sites.

Two papers, in particular, highlighted the transnational dimensions of alcohol and drug history. Robert Eric Colvard’s paper reveals that Pussyfoot Johnson, an ardent American Prohibitionist, became an unwitting pawn in the hand of nationalists when he traveled to India in the 1920s. And Sidsel Eriksen demonstrated some ways in which American temperance thought, which first arrived in Denmark in the 1840s, resonated in another national context.

Also noteworthy were papers about less familiar sites. Charles Ambler focused on alcohol and the rhetoric of postcolonial modernization in Zambia, a country that became the WHO’s case study of Third-World drinking after decolonization.

Looking at the American South, Joseph Beilein, Jr. described how moonshining became an act of cultural resistance to both Confederate taxation and Northern occupation. North of the Mason-Dixon line, Josh Steedman tracked the rise and progress of temperance organizations in Norwalk and Sandusky, two towns in northern Ohio’s Firelands district that have not been extensively studied.

Interesting Sources: From the WCTU to Jazz Lyrics

Kim Drechsel, a Dwight Historical Society historian, showed off his collection of Keeley artifacts and memorabilia. But “I’ve Been to Dwight” also highlighted some fantastic regional historical sources beyond those associated with Keeley. Janet Olson, volunteer archivist at the Frances Willard Historical Association (on Twitter @FrancesWillard) in Evanston, IL, described their rich collections. Also from Evanston, David Trippel showed off his extensive collection of temperance literature, which is fully catalogued on WorldCat.

Some of the papers presented research on especially interesting primary sources. I was particularly drawn to Sarah Lirley McCune’s use of coroner’s inquests to study women’s drinking deaths, Bob Beach’s examination of jazz lyrics in an era of “reefer madness,” and David Pratt’s analysis of Dashiell Hammett’s detective novel Red Harvest.

Dwight Historical Society

The Country Mansion, which was built as the Oughton family home before serving as the Keeley Institute’s patient lodge, offered a historic venue for the conference. Special thanks are due to Mary Flott, president of the Dwight Historical Society, and the volunteers who welcomed us warmly and arranged a bus and walking tour of Dwight.

The Country Mansion, site of the “I’ve Been to Dwight” Conference

The tour included a reenactment of a temperance scene at the train station, historic houses of prominent Dwight families, the First National Bank of Dwight, the Keeley Institute building (currently the William Fox Developmental Center), and the Keeley family mausoleum at the cemetery. In the upstairs lobby of the Fox Center, the stained glass depiction of the five senses that addiction debilitated, was for me, the highlight of the tour. And after the conference closed on Sunday, the Dwight Historical Society reenacted the original AA Roundup, an event the Keeley Institute hosted until its closing that brought together recovered alcoholics who had undergone successful treatment.

Temperance reenactors

The Keely Institute Building (now the William Fox Developmental Center)

Tour of the Keely family mausoleum