Challenging the User Paradigm: Comic Book Characters, 1937-1954

- Bob Beach

- Mar 19, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

Editor’s Note: Today’s post comes from contributing editor Bob Beach. Beach is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Albany, SUNY.

In a prior post, I’ve examined popular culture (jazz), as a unique perspective on the potential motives of marijuana users through the mundane lyrical descriptions of users in jazz songs. I’ve suggested that Cab Calloway’s “Reefer Man” represents a narrow but perhaps authentic representation of use in poor urban communities. Comic books are certainly different sources than jazz songs. Their creators are far less prominent than the characters they create and the audience for comic books (young boys and girls) are much less connected to the creation of the cultural form than audiences in jazz clubs, and, at least theoretically, to the environments and situations described in its pages.

However, the representations in the comic books do present a range of possibilities for users that go well beyond the addict or non-addict binary that was popular at the time. It also suggests that complex understandings about use pre-date the era of official tolerance of marijuana in the mid ’60s into the mid ’70s. It is also worth mentioning here that at least some official attention was paid to representations in comic books by the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, which looked into problematic representations of sex, violence, and, to some degree, drug use therein.

Starting from the binary of user v. non-user, the handful of comic book stories that I’ve been able to read make several distinctions between the two categories. Users are either natural users like Weedy Smudgeon (where use is their character) or unnatural users (where use intervenes and changes a character). The former group, in the sample I viewed, were almost exclusively ethnic others. The latter group were almost exclusively young (white) adult men and women, and their use results in (generally) two possible outcomes: a descent into addiction with dire consequences (jail or death), or redemption where a user corrects his/her behavior to either become a hero himself (if they are male), or a cautionary storyteller (if they are female).

“Non-user” is a much more slippery category, and indeed, the function of non-users in these stories becomes clear only as exceptions that prove the rule. One subcategory of non-users is “good guys” (title heroes, family members, and law enforcement), and the other is “bad guys” (the organized criminal rackets that import, distribute, and sell the drug). Good guys don’t use for obvious classic-era comic book reasons, but the rackets don’t use precisely because they know the dangers the plant poses, particularly the addiction (and thus profit) potential of marijuana, and after the mid 1940s, of marijuana-to-heroin.

But they were also well aware of the specific dangers of the drug that they deal in. This is demonstrated by two examples of the rackets specifically using the drug to get innocent victims to do their bidding. In 1941, The Dart’s sidekick Andy (figure 2) and Plastic Man (figure 3) are plied with marijuana in this fashion. The rackets themselves do not use. In fact, when a naïve drug runner wonders aloud what all the fuss was about, he was physically attacked by his boss (figure 4).

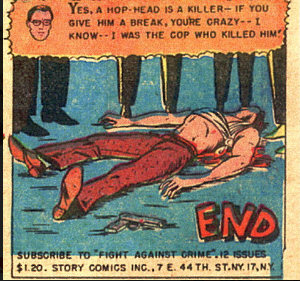

The innocent user characters’ distinctions are much more blurry and, while most characters have a clear bad or good persona, there is a blurring of distinctions. Several of these innocent victims lose their innocence and either end up dead or hopelessly addicted to marijuana or heroin. The fates of these tragic innocent victims are on display during the dramatic endings of Wallace Reagan (figure 5) in “Hopped up Killer” (1941) and Howard Martin (figure 6) in “Worse than Murder” (1952).

The redemption stories hold the most interest in the context of challenging binary assumptions about use. To be sure, redemption stories are fairly standard in the comic book genre, but within the larger context of portrayals of drug use, the notion that a user could reverse the downward descent from naïve marijuana use into heroin addiction to death is significant. Also relevant here is the assumption that men and women are redeemed in different ways, the former through rehabilitation and/or heroics, but the latter only through penance.

That’s what brings us to Jeff Dean. We are introduced to Jeff during the first few frames of “The Dart and Ace” (1941) as he’s attacking his teacher Miss Tilbury. By the end of the story, Dean foils the racket and saves the day. (Figures 7 & 8) Similar experiences befall a group of young kids duped into running marijuana for a local paragon, but who turn on Mr. Cratchett and are considered for acceptance into Mr. Universe’s athletes club (figure 9), or a young Jack Winters who murdered a police officer but will get off “lightly” due to the real blame being placed in the Mexican smuggler (figure 10).

Women had fewer options for redemption, but avenues to that end did exist for female characters in these stories. Rather than re-assigning blame or transitioning from hero to villain, however, women are limited to harsh penalties that encourage these women to “tell their stories” to other young women in the first-person. For women too, their initial innocence, which unlike an uncanny number of male characters introduced to marijuana by a peddler at a party because they left their pack of cigarettes in the car (and the peddler offered on of his), was tied directly to un-womanly ambition and romantic agency. Gloria Welsh’s desire to pursue a career in Hollywood ensnares her whole family (figure 11). Her younger brother Frankie, who was running shipments to clients, was killed when the delivery business introduced him to marijuana use and he descended into addiction. She “told her story” in “I was a Racket Girl” (1949).

Other women spiral into the cycle of addiction through ill-advised relationships with men. Both Claire (“My Scandelous Affair,” 1954) and Louise (“I Was a Musician’s Girl,” 1954) get addicted to marijuana as a consequence of choosing the “wrong” of two men to pursue. By the end of both stories, the women had been reunited with the “correct” man and are miraculously fine (but still hope to prevent this in other young girls by telling their stories).

Given the limits of comic books as representational sources, the spectrum of use that appears in a selection of comic book stories collected between the 1930s and ’50s presents a subtle challenge of conventional descriptions of users circulated in law-making and law-enforcement circles during that time, all of whom tended to characterize users more like Mr. Smudgeon (at least, as conventional wisdom goes, until the 1960s) than like Jeff Dean or Gloria Welsh.