Addiction, History and Historians: Alex Mold’s Response

- Alex Mold

- Mar 6, 2012

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2023

Editor’s Note: Our roundtable on addiction, history and historians continues with a commentary on David Courtwright’s essay from Dr. Alex Mold. Alex is currently Lecturer in History at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, where she has been since 2004. She received her PhD in Modern History from the University of Birmingham, and (in 2008) published Heroin: The Treatment of Addiction in Twentieth-Century Britain (Northern Illinois University Press). More recently, Alex (together with Virginia Berridge) has authored Voluntary Action and Illegal Drugs: Health and Society in Britain Since the 1960s (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). We are delighted to post her commentary on David’s essay. If you’re new to this roundtable, feel free to go back to the introduction, or read Nancy’s Campbell’s response (the first in the series).

Addiction Acrobats? A Response to David Courtwright, ‘Addiction and the Science of History’, Addiction, 107:3 (2012) pp. 486-92

David Courtwright is an adept addiction acrobat; deftly balancing on the high wire that spans the two worlds of addiction science and addiction history. In ‘Addiction and the science of history’, he makes a powerful case for what historians and scientists have in common, where they differ and what they might learn from one another. The piece is written with the lucidity and verve we have come to expect from one of the field’s leading historians, and also offers a brief survey of some of the key works in drug (and to a lesser extent alcohol) history over the last 30 years. Courtwright locates this scholarship on a spectrum that runs from ‘oppositional’ (critical of the status quo) to ‘accommodationist’ (mildly reformist) to ‘dominant’ (conservative). Unafraid to hint at addiction history’s cardinal sins as well as its cardinal virtues, the essay represents an attempt at outreach to a scientific community who, Courtwright suggests, need us as much as we need them.

Can you spot Prof. Courtwright in the line-up?

The call for historians to engage with the contemporary science of addiction, made by Courtwright in his keynote lecture to the Alcohol and Drug History Society conference in 2004, and published in the society’s journal in 2005, has been echoed by other historians such as Howard Kushner and taken up by (among others) Nancy Campbell, Tim Hickman and Virginia Berridge. The development of what Howard Kushner has a called ‘a cultural biology of addiction’, bringing together biological and social perspectives, is an important project. The challenge, as I see it, is to absorb this work without ‘going native’: to take on the recent developments within addiction science but at the same time maintain a sense of critical distance. Drug and alcohol historians, well versed in the knowledge-power play of addiction science over the last 200 years, are able to expose the socially constructed dimensions to addiction as they change over time and space.

All of this I think David would agree with. My concern with the essay is not so much

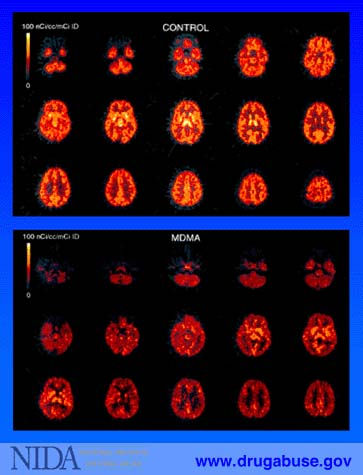

The Imaging of Ecstasy/The Ecstasy of Imaging

about what is said, but rather the way in which it reflects, and thus may serve to reinforce, two dominant approaches: one scientific and the other historical. Contemporary addiction science, as it is presented in this essay, is closely allied with what Courtwright calls the ‘NIDA paradigm’ which regards addiction as a chronic relapsing brain disease, albeit one with social and genetic components. Yet, neuroscience is not the only game in town and nor is NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) the only agency interested in addiction and associated issues. Browsing down the contents list for the issue of Addiction in which Courtwright’s essay is published reveals a wide variety of addiction research, taking place in a range of settings, and making use of numerous disciplines and methods. Articles by scientists, physicians and social scientists offer insight into aspects of addiction such as the relationship between childhood depression and problem alcohol use, and the transition from first illicit drug use to injecting drug use amongst users in the Appalachians.

Of course, not all such work contradicts the brain science model, but the diversity of current addiction research should not be ignored. Indeed, the NIDA paradigm is far from being universally accepted. In a recent forum in Addiction a number of commentators questioned the extent to which the chronic relapsing disorder model was an appropriate way to view alcohol dependence. Historians may think that they can hold themselves apart from such debates, but the difficulty with the chronic relapsing model is, as Jacek Moskalewicz points out, that it individualises drug and alcohol problems. Locating addiction in the brain of the addict downplays the social, political, economic and cultural dimensions of the issue, the very elements that historians tend to be concerned with. By engaging with the NIDA paradigm are we in danger not only of unquestioningly accepting the dominant view, but also of doing ourselves out of a job?

The explosion in drug and alcohol history in recent years would suggest that if this were the case then there would be many of us looking for alternative employment. Courtwright does a valiant job of referencing important work on the USA, Britain and China, but there is a much broader geographical range of scholarship covering Africa, Asia and continental Europe. It would be deeply unfair of me to criticise Courtwright for failing to engage with this literature in such a short piece and one that has a different target in mind. My point is not that the essay is insufficiently global in its outlook – Courtwright has ably demonstrated that he is more than capable of such work elsewhere – but rather that there is an implicit tendency to see the evolution of addiction in the light of the North American history of drugs and alcohol. There is a sense that developments elsewhere in the world are measured against the ‘norm’ of America. Take Courtwright’s remark that a fluent English-reading graduate student could ‘gain a knowledge of the history of addictive substances’ in a semester’s reading. What if, instead of being able to read English, that student could read half a dozen other world languages? Would he or she find the same narrative that arcs through the American history of addiction, or a different one?

I don’t know, but I hope to find out. I am currently involved in research that is part of the European Commission funded Addiction and Lifestyle in Contemporary Europe Reframing Addictions Project. One of the work packages that make up ALICE RAP (as it is known) is concerned with the history of addiction throughout Europe. Led by Virginia Berridge, the work package draws on historians and social scientists from across the continent to examine the history of addiction in countries such as Britain, Italy, Sweden, Poland and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Although work has only just begun, we have already found important similarities and differences in the development of the concept of addiction in different countries. What is also significant about this research is that it is embedded within a much larger network of projects that examine many aspects of the multi-faceted problems posed by addiction. ALICE RAP brings together over 100 researchers from 25 different countries and 29 different disciplines. Areas of research include: the ownership of addiction; counting addiction; the determinants of addiction; the business of addiction; the governance of addiction; and addiction and the young.

Graphic Interdisciplinarity

To engage with the contemporary science of addiction we should do more that ‘take a hit of neuroscience’ as Courtwright advised in 2005. To do the field justice we need to experiment with a range of other scientific approaches. This suggests that as well as being addiction acrobats, drug and alcohol historians need to be pretty good jugglers: keeping multiple disciplinary balls in the air while at the same time maintaining our sense of balance. Courtwright’s essay thus marks the beginning, not the end, of a dialogue with the science of addiction that stretches beyond the brain.